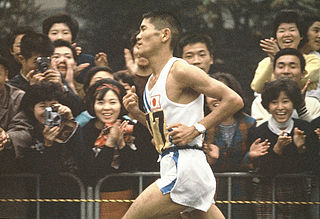

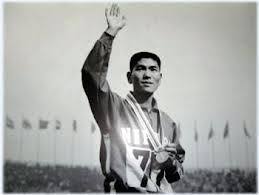

Entretien avec Christophe Lemaitre: Bronze medalist in the 200 m. at the Rio Olympics, French National Record holder in outdoor 200 m. (19.80)

English Transcription below

John Knych (JK): When I was in the train, the train passed Culoz, you grew up there?

Christophe LeMaitre (CL): Culoz.

JK: First I’m curious of your childhood there, because it’s a little town.

CL: Yes a little village.

JK: 3000 people?

CL: Yes, around there.

JK: So your childhood there, what did you do for fun? When you were little?

CL: There was not a lot to do, to be honest. Spend time with friends, play soccer, go outside.

JK: You have two older brothers?

CL: Yes.

JK: Are they also fast?

CL: No.

JK: Do you get along with your brothers?

CL: Yes, we got along, they were athletic too, played sports, like I did when I was a kid, but they didn’t sprint.

JK: Why?

CL: They didn’t have track at Culoz. And it didn’t interest them.

JK: And what do you parents do?

CL: My mom didn’t play sports. But my father played a lot of sports in the past, he was athletic. He did swimming and wrestling. But not sprinting.

JK: And I read that you played handball and rugby?

CL: That’s right.

JK: And that you found running by accident. There was the Tour de fête de Belly?

CL: Belay

JK: When you were 15 years old? Are you able to tell me about that experience? When you found the sport?

CL: Yeah but it wasn’t really by accident. We can say that…with my mother we were looking for another sport.

JK: Why?

CL: Because all of the other sports I did weren’t interesting. Or, it’s not that they weren’t interesting but…I wasn’t ah…I wasn’t enthusiastic. I didn’t have the desire to look for new experiences in those sports. And so while I was searching for new sports, I had my classmates and my gym teacher who were doing sprints and who said that I ran fast. So we looked for a place to prove myself. And at Belay there was a coach who tested athletes for the 50 meter sprint.

JK: Yes. Was it Pierre Carraz?

CL: No he was my first coach. The one who found me was Jean Pierre. And he started training me. He did the test and told me that I sprinted fast and that I had the quality.

JK: That you were talented?

CL: That’s it.

JK: How much time after this experience did you meet Pierre Carraz [his first coach]?

CL: I believe it was two years after, I think in 2005, or in 2007 I met him and started training with him.

JK: How did you meet Pierre?

CL: I think the first time was at a competition? Or I think it was the first time I went to Aix-les-Bains for training. It was there that he started to coach me. That he wanted to train me.

JK: And when did you know that you could succeed with running? In international competitions?

CL: I believe that it was…in 2007. With the Junior World Championships. I qualified in the 100 and 200 meters. And I finished 4th in the 100 meters and 5th in the 200 meters. And at the time in a new group for junior athletes. And I did that after only two years of training.

JK: That’s crazy. You started at 15 years old and three years later you were champion at the World Junior Olympics.

CL: That’s right.

JK: That’s unbelievable. So during those three years you were always working? Did you progress gradually, how was it?

CL: Of course I progressed little by little. In every race I beat my personal best time. However I didn’t really know a lot about training. I started with three sessions per week. The year after 4 sessions. There you go, I trained as much as the people in my athletics club.

JK: And immediately you got used to the life of an athlete? A serious athlete? Just after finding running did you get used to the rhythm of an athlete’s life? Or was it difficult in the beginning?

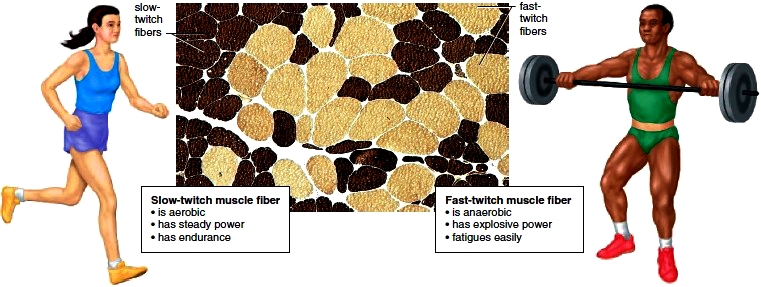

CL: No it was difficult because during some training sessions I had difficulty with…with long sprints. With 300 meters or 400 meters, I was really far behind my teammates.

JK: Why?

CL: Because I was bad. *Laugh/exacerbated sigh concerning the poor question* I didn’t have endurance. At the time I…in fact the cardio and endurance was very complicated for me. Aerobic sessions were horrible for me. It was really took 5 or 6 years for me to be able to handle those sessions.

JK: That’s interesting because the 200 meters is really your event. And of course that requires more endurance than 100 meters.

CL: Of course

JK: So your endurance improved little by little.

CL: That’s right.

JK: When did you realize for the first time that you could win a medal in the Olympics? After 2008 when you won the Junior Olympics?

CL: No it was much later. I think it was after Daegu. 2011. World Championships. Because there I ran the 19.80, the French 200 meter record. And I won the bronze. So I said to myself, the next year, in London, maybe I have a chance. To win a medal.

JK: So before Daegu you didn’t think that you could win a medal?

CL: Before? No. Because I was aware of my times in the beginning. 20.83. At the World Junior Championships. So when I saw sprinters running faster than 20 seconds, I knew I was far away. I was thinking really that I was incapable of achieving that level.

JK: But you did it. I read in an article that you said that if Teddy Tamgho can do it, so can I. Was he an inspiration for you?

CL: For the Junior Olympics?

JK: Yes.

CL: In fact no because I didn’t see him. While he was jumping I was preparing for my event. So when I finished I didn’t know that he was the World Champion.

JK: Okay. What’s more important to you, records or medals?

CL: Medals. Without a doubt.

JK: What is your relation with your coach? You told me that after two years you found Pierre Carraz. Today you work with Thierry Tribondeau.

CL: To be clear I am still working with Pierre Carraz. I have two coaches. It was Pierre who asked Thierry to join us for helping with my preparation.

JK: And your relationship with Pierre Carraz. Tell me, do you have complete confidence in him, do you call him every day, how do you work with him?

CL: Yes he is someone who I have confidence in for my training and preparation. He is someone with a lot of experience. And he has an eye for seeing the strengths and weaknesses in an athlete. And so yes I have complete confidence in him because he can prepare me well for the major competitions.

JK: I read in article in France Bleu that Pierre said, “We know where we are going.” Just after your performance in Rio, he said “That night we asked ourselves how we can prepare for the Tokyo Olympics.” Is that true?

CL: Well, I wasn’t there. But yes I heard that Triboneau called Carraz to start planning for the Tokyo Olympics.

JK: Wow. Did you party after winning the bronze medal? Or did you start working immediately after?

CL: After I finished the games, yeah I went to Club France to celebrate with the French fans who came to Rio to support the French team. I celebrated with them, there you go.”

JK: I saw a video of your teammate on the bus, he wasn’t sure that you had won because it was so close, the rest of the team of France, they were excited. You choose to study and prepare here instead of Paris? For what reasons?

CL: The atmosphere of Paris, I don’t see myself living there, to be honest.

JK: Why?

CL: It’s totally different. I need calm and a place to relax. It moves 24/7. Everything is grey. There’s all these buildings. There are no mountains or forests. There’s nothing. There’s no nature. It’s horrible. The people are always hurrying and are unpleasant. To visit, sure, but to live, no. It’s not my thing.

JK: Soon you are going to begin intense training for Tokyo. Can you share with me what your life is like when you are in the most intense part of your training? The daily routine?

CL: I discuss with my coach to prepare. All the work that we have to do. Five or six sessions per week. With a part that is short sprints, long sprints, a lifting session, and a general physical session. So in the winter we build the base. The goal is that we compete internationally. In the winter we go someplace with better weather for training. Because it is really quite cold here.

JK: Lot’s of snow?

CL: Not really snow, because of the lake next to us, it creates a micro-climate. But yes were are next to mountains so it gets really cold. So sometimes we go to the south. Or to another country. To find better conditions. Then the summer arrives and we need to run fast because there is the selection for the Olympic team. And it’s early. I think it’s in June. I hope I’m not making a mistake with that. But we have to run fast early. If we hope to make the list.

JK: My best French friend wanted me to ask you this question: how many kilometers per week do you run? In general? Do you know? [Christophe thought I asked: how fast do you run? I didn’t understand that he didn’t understand my question right away.]

CL: How many kilometers/hour? 40 kilometers. Between 40-42. After, to run 10.00 for 100 meters you have to run an average of 37 kilometers/per hour.

JK: But how many kilometers do you run per week? Total?

CL: Ah, we don’t run lot. For example, we run more in the winter. 3 laps of the track and we’re finished. The we do other things.

JK: How do you relax? I read that you like Overwatch? Is that your favorite way to relax?

CL: It’s not necessary my favorite way to relax. It’s mostly a way to pass the time. To distract myself. I play the saxophone. And there are other things. I stay busy.

JK: I’ve talked with the athletes who are constantly thinking about their sport. But you, when you’re not running, you try to do other things and not think of track? Because it’s so intense. Do you follow the success of other athletes? How much are you a student of the sport?

CL: In general yes. I follow the other athletes’ performances. Diamond league. World challenge. In France too. It interests me. I love watching, with my friends, the competitions. I love my sport.

JK: I read that your hero is Usain Bolt. I saw a video where you are in a photo with him. How are you inspired by him and what have you learned from him? I read that he has respect for you and for your victory. Have you learned things from him?

CL: Usain Bolt…I think of him first as an adversary like the others. Despite him being the best sprinter in he world, and conquering so many others, I always considered him like any other adversary. Like any other sprinter.

JK: So he wasn’t really your hero, just another competitor?

CL: Yes, exactly. But I always considered a race against him as a chance…because you know that the race is going to be fast when there’s Usain Bolt. So it’s necessary that you take advantage of this opportunity, to try and hold on, to not lose your head, to run fast.

JK: Would you say that Jimmy Vicaut is your rival? Because you ran with him in the relay?

CL: For Jimmy it’s like Bolt, he’s a competitor like any other. When we were in the relay together, things change, we were teammates, we worked together, to win the relay. But beyond that, I didn’t consider him as being more important than the others because he is French.

JK: So you wouldn’t change your training?

CL: No, he trains in Paris, I train here. We only see each other in big competitions. But that’s it.

JK: Now I have a difficult question, what did you feel in Doha when the team didn’t finish the race. How do you handle the obstacles, the injuries, the losses in your career? Because I read in an article that you said something very profound, you said, “The secret of sport is to not be imprisoned in your previous race.” Can you explain this phrase? It’s powerful.

CL: I said that because there was a time when I was practically 100% consumed by athletics in my head. And I did nothing on the side. All I did was training, recovery, working with the team, competition. And I think I was into it too much. I was always consumed by ambition, to perform well, to succeed, and so during the moments when it was difficult, when I wasn’t performing well, or when I was injured, I had nothing on the side to forget it, to think of it less, to move on. I was completely disappointed and always thought to run and run to rid myself of the bad races or injuries, etc. Except I wasn’t improving and I was frustrated because I was working more than I had in previous years when things were working, and I didn’t understand that I was training more and harder without the same results. So I changed my method, saw a Sports psychologist to help me put my ideas in order, to feel mentally better, to be capable do succeed for me. Because before I run to shut up the critics to show others that I’m capable of running fast. And that my career wasn’t behind me. I changed that by running for my own pleasure. So when I had injuries or low moments I was able to stay positive and keep my head because I knew that the critics were just sport and it’s a part of my life, but not my whole life, I do other things that I’m passionate about and that I love. It’s going to stop someday so I’ll make the most of it now, but I’m not just Christophe Lemaître the athlete but Christopher Lemaître who does athletics, not just an athlete, I’m someone just like anybody else, athletics is not my whole life, just a part.

JK: Concerning the question of the critics, I read that your coach said, “It’s part of the daily routine of high-performance athletes, when you’re in the light you’re exposed to critics, if you’re not being criticized you’re in your little garden doing little chores.” For you, do you follow or ignore the critics? Do critics feed you or do you say to yourself, “they’ll say whatever they want, I’m me, and I don’t give a shit.”

CL: At an earlier time I read a lot of the critics and like I said I read to shut them up. But I don’t think that it was good thing. Because they don’t know how you train. They feel they can judge you but they don’t know your training. They don’t know where you’ve come from, your moments of doubt, the extremely difficult moments. And that pisses you off. You want to show them that they’re wrong. That I’m someone who can still perform well. And I’m not someone who does nothing, but that I work really hard. And now I’ve learned to ignore it all. When I have bad performances, I don’t look at the critics at all. That was just a phase. I think that no matter what happens there’s always someone who will be critical of you, even when you do things well. And they give criticism that’s not at all constructive. So it’s necessary not to listen to them. They can scream all they want. Keep living your life how you know how.

JK: So how do your previous experiences in Rio influence your life today? I read that Vicaut said that, “In Rio, you were ranked 35, and you placed 3rd.” And I read that Doha is a trampoline for the Tokyo Olympics. So now…I read that your objective for 4 years has been Tokyo. So now how does your experience compare with your experiences before Rio? Because before Rio you had injuries. How do you feel now? How do you feel compared with the year before Rio?

CL: The year before Rio it was complicated because I had a lot of injuries. And I didn’t make the finals of the World Championships. In addition it was just complicated. But there was something that I knew: if I wasn’t injured I knew I could run really fast because the only times I couldn’t run fast were when I was injured, and the injuries affected my training. I knew that if I had a year with no injuries or very few injuries, I could succeed. So the goal for Tokyo is to avoid injuries as much as I can, to give attention to any little pain, to get out of the psychology of injury. If I feel bad I take a week off. It’s necessary to be vigilant, to every little alert of the body. And don’t fear injury. It can happen at any time. An injury can be a sign that I need to take a break before a worse injury. Be careful, be vigilant. Be capable of not training. Better to miss a day here or there than get injured and miss weeks.

JK: You have become more skilled to read and watch your body. To say: now, I need rest.

CL: That’s it.

JK: I watched this video, the revenge of the unliked. France TV sports. Have you seen it?

CL: No.

JK: It was the..

CL: Oh yes, the television segment.

JK: Yes, and I know it may be difficult to talk about it, but can you tell, your adolescence wasn’t easy. I learned that the other students weren’t kind to you. In what way were the other students cruel to you? I read that when you were 11, you closed your off. Can you talk about this period in your life?

CL: Yes, it lasted all through middle school. It was a lot of mockery. The remarks which hurt me. And even sometimes happened outside of school when I crossed the students who were mocking me.

JK: And this part of you life, how did you keep going? When the others weren’t kind, how did you fight against it, or deal with the mockery?

CL: I never really was able to deal with it. I was really very timid. I didn’t dare…I had difficulty talking, the only time I dared to do something, it came back to hurt me. It wasn’t working. When you are alone in a group, even when you try to fit in, it doesn’t work, you feel like everything is against you, you can’t do anything. It’s complicated to get out.

JK: Between 11 and 15 you were mostly alone?

CL: That’s it.

JK: And when you found sport it opened a door for you? And you life completely changed?

CL: Yes.

JK: I read two phrases online: “He will function better not caring about the others…he was not going to struggle or shed tears against their mockery.”

CL: Hmm-hmm

JK: When you said that…the recognition of others…I would like friends…but you didn’t have the way to make friends. That second phrase: not going to shed tears against their mockery. What does it mean?

CL: It means…when the students mocked me, I didn’t know how to react or change it, how to get out of it. In the beginning I thought it was pass, the it was just something fleeting, and that they will stop, when they’re older, or find someone else. But it never stopped. And I didn’t know how to get rid of it.

JK: I read that after Rio you were proud to be France. Is that true?

CL: Yes. Proud to win a medal to France. Yes I had the desire to win a medal for France. When I had it I was happy to be able to be with the other champions. In Paris. To be with those who supported me.

JK: What would you like Americans to know of what it means to be French? I know it’s question a little bizarre.

CL: Yes. Pffff. I think that it is the same for Americans, we are proud of where we come from, I know that Americans are very patriotic, but there’s still a pride of being French, a cultural pride. For athletes there is this desire to make France shine, whatever the way you do that, a pride of singing the Marseillaise. A strong pride of being French. Despite the multi-cultural aspect of France, people from different regions, people are still proud of being French. People are happy to see athletes who shine.

JK: The 200 meters is your specialty. What part of the race are you trying to improve right now? To achieve the next level?

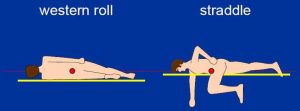

CL: I think I want to improve every part. But the part I can improve the most is probably the turn. The first part of the turn, it’s all right, but the second part of the turn I am capable to move better into the straight and to hold my speed and to conserve it. I can improve that. I know that I can hold my speed right to the end. It’s just that part of the turn which is a little complicated.

JK: Of course Tokyo is in your head right now. But 2024 the Olympics are in Paris. Is there a part of you that thinks: if my body can hold on, Paris is a possibility? Or is too far to think about?

CL: Yes at the moment it is a bit far away. I have always had the habit to think year by year. For 2024 I’ll have to think later, if my body still capable of running fast? Also mentally do I still want to keep training? To continue to keep trying to reach a higher level.

JK: Is it tiring, in general, the life, your life, the life of an athlete? Or have you found a good rhythm with things like the saxophone?

CL: I think that it is necessary, to endure, you have to be capable of doing other things, because it’s true that it’s exhausting to think 24/7 of sport, I think it’s important to, like I said, think of other things. To liberate the spirit and the head, other activities.

JK: And you study here, in Aix-les-Bains, also, industrial…you’re at university?

CL: Not here. Annecy. Business collective communication. Yes it’s important to have other projects.

JK: Have you visited the United States before?

CL: Yes, twice, 2-3 times for my sporting internship, also a school trip.

JK: So you ran there.

CL: Yes, 400 meters with my club. The team of France was presented. It was super, great. And I had did 100 meters and I won there.

JK: Do you think that after your career you want to stay in the world of athletics, to be a coach, or other things, or do you not think of that?

CL: Of course I think of it that is why I have my studies. But still the future is still vague. To stay in the sport as a coach…I could…or do other things…do something completely different. Social media, management.

JK: When I watched the video of your victory in the Olympics. I saw that you have a routine before your race. How to you relax before a competition. How do you prepare right before a race? How do you relax? Like before the Olympic race?

CL: In general, I stay relaxed. For me the stress of the competition just comes a few hours before the race. And in general before that I’m rather relaxed. I watch TV, take a nap. Even the day of the competition I can sleep thirty minutes in the afternoon. It’s not a problem. I pass my time tranquilly.

JK: And now you work with your coach, is it the same time with Pierre as with Triboneau?

CL: Now in fact the preparation is created by both of them. They make it together. For the season. There’s not time with one, time with the other. They are both there and they observe me and give me their opinions. There’s not one or there other.

JK: I saw that you are the first white man to run faster than 10 seconds for 100 meters. I read that you don’t like this title. I read that you don’t like this title. What do you think of this though, to be the first man under 10 seconds for 100 meters?

CL: Yes it’s something that I don’t like because it ignores the important fact that I broke 10 seconds that I’m a man who is capable of that, and at the time it was new French record, which is very rare for France at the time, and that was totally ignored for the fact that I was the first white man to break 10. I prefer to be judged in the domain sportive. The color is anecdotal.

JK: What do you think that you can improve more easily, the 100 meters or 200 meters? Now you have the record of 200 meters. And Jimmy Vicaut has 100 meters. Do you think that you can run faster in the 100 meters? Or do you prefer to concentrate on the 200 meters?

CL: I think that, in my opinion, it’s preferable to concentrate on 200 meters rather than 100 meter because that’s where I’ve proved myself and that’s where I have the better chance of earning a metal, in relation to my potential. But I think I’m still capable of running fast in the 100 meters. I think it’s important to run the 100 meters to prepare for the 200 meters. Running the 100 meters will improve my speed. The pure, basic speed. To prepare for the 200 meters.

JK: Do you have the gold medal in your head for Tokyo? Or do you think: I just want to run the fastest that I can? If I win, I win.

CL: Of course it is my dream, I think every athlete has it, to be the Olympic champion. But I know that there is lot of unknown in sport. More important is to just want to be in peak form for the competitions, for the Olympics. After to be capable to bring out my best race, my best moments, and to medal.

JK: When you think of your adolescence, is it like another life for you? Or when you think of that time are you more motivated?

CL: Not it’s totally finished. I don’t think of it at all. Now is time when I think of myself and my projects, I live my life serenely, without a problem. I feel good. I’m happy with what I’ve done and I’m happy with what I do, that’s the main thing. It’s the mocking of the critics, it’s my performances that count.

JK: And your family, your brother, they are proud of you? You’ve had a lot of success. What do your family think of your victory.

CL: Yes well of course they are happy and proud, they have already told me, of course. I think that any family would be proud and happy to receive this honor in sport, of course. It was surprising for them. But they follow and support me.

JK: Christophe, thank yo use much, it was a pleasure for me. The coffee is on me.

CL: Thank you.

JK: I think that’s all I would like to talk with you about…*pause*…and again, pardon me for my French.

CL: No, it was comprehensive, it’s good.

*