“I believe in god, only I spell it Nature.”

-Frank Lloyd Wright

In 1932, it appeared that Frank Lloyd Wrights’s career as one of America’s greatest architects was over/had gradually gone down the drain. At the age of an 65 he hadn’t completed a major project since the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo in 1923:

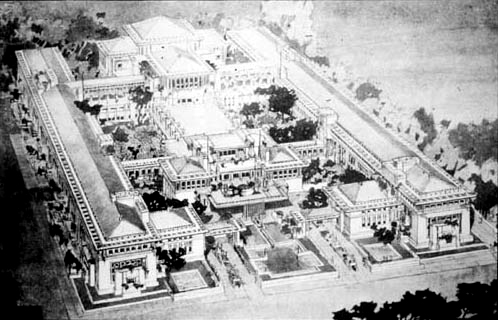

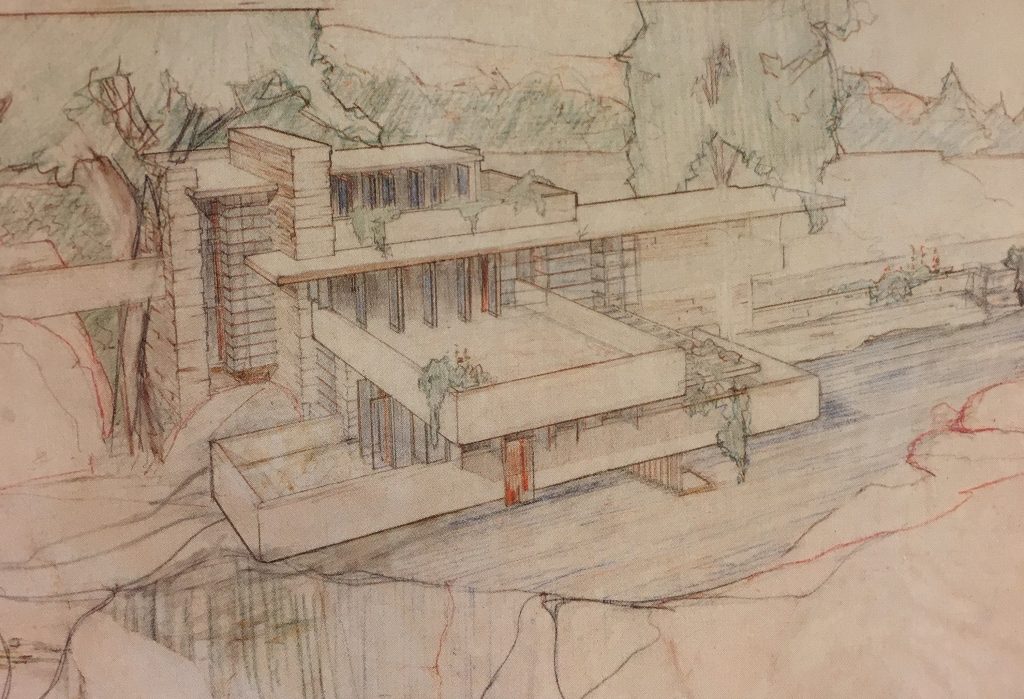

Final Perspective Drawing below (700+ drawings were created for this project):

Even though the Imperial Hotel seemed to solidify Wright’s fame at the time, especially as it survived an earthquake three months after completion, nine ensuing years of small projects significantly diminished his reputation. Colleagues thought he was dead. Critics considered his work anachronistic. The Great Depression was strangling possibilities for architectural projects, so in 1932 Wright did two things outside of his field with would open the door for a career-revitalization:

1.) He wrote an autobiography. (“Early in my career…I had to choose between an honest arrogance and a hypercritical humility…I deliberately choose an honest arrogance, and I’ve never been sorry.”)

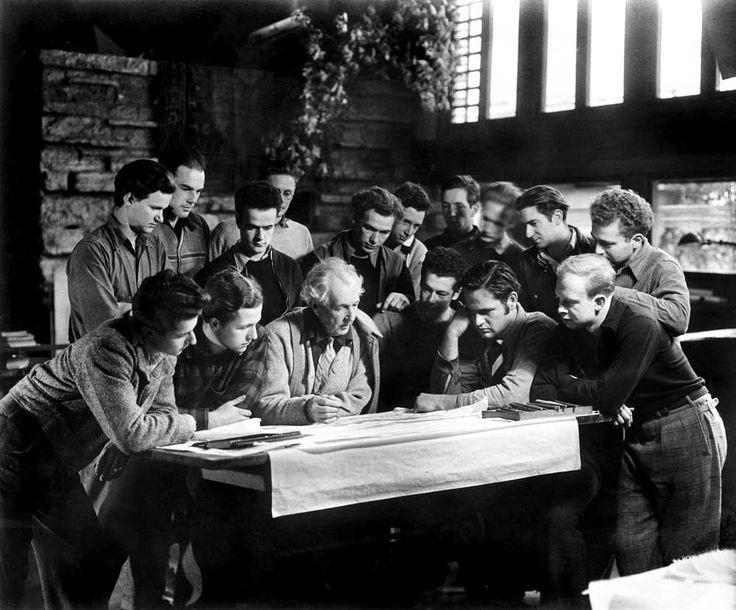

2.) He became involved in pseudo-education at his home to help pay the bills (i.e. clean my bathroom and I’ll show you how to stabilize a roof with a buttress). He founded the Taliesin Fellowship:

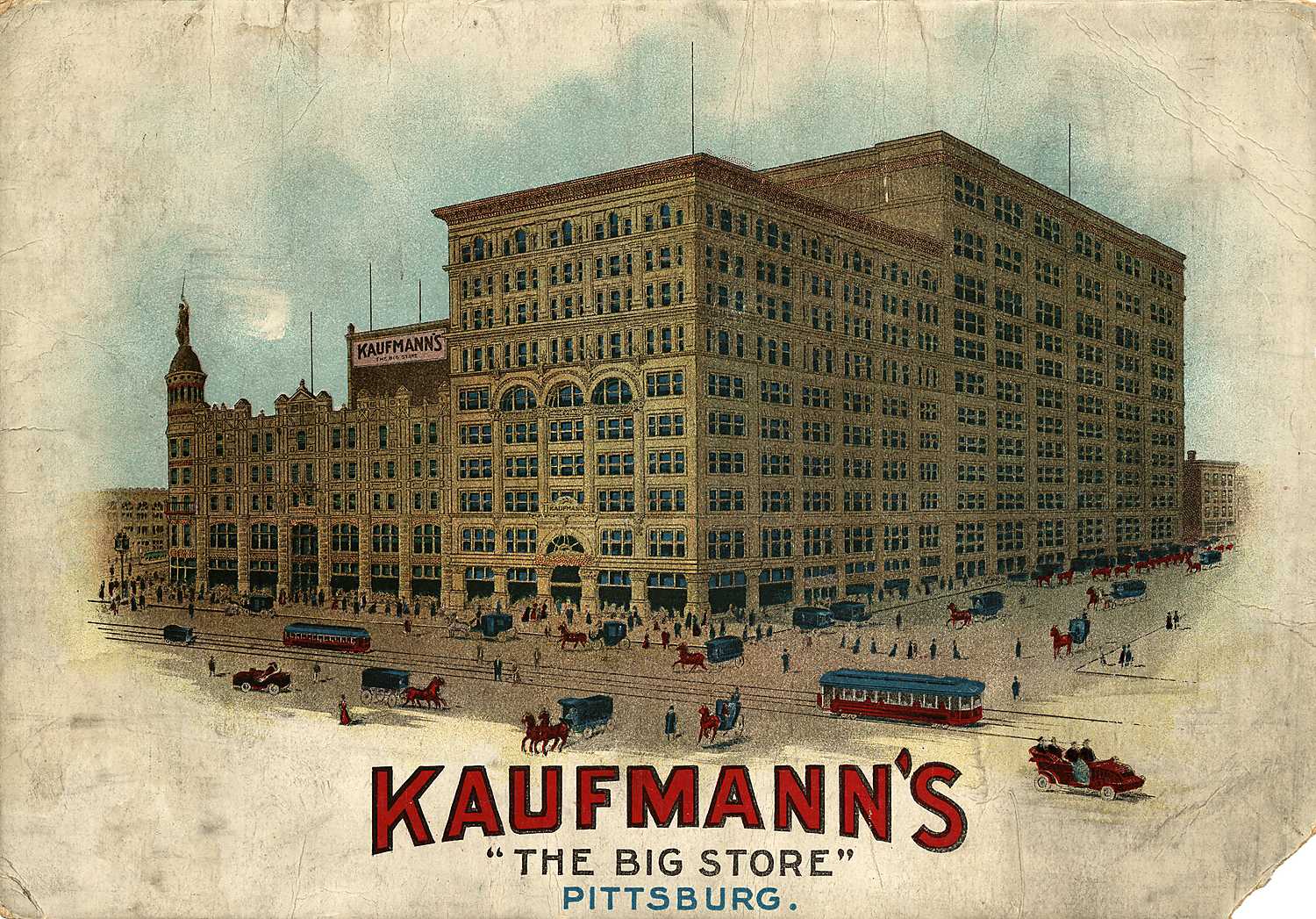

Meanwhile, a young man named Edward Kaufmann Jr. was studying painting in Italy and sipping cappuccinos. He was the only child of Edward J. Kaufmann, the owner and president of Kaufmann’s department stores:

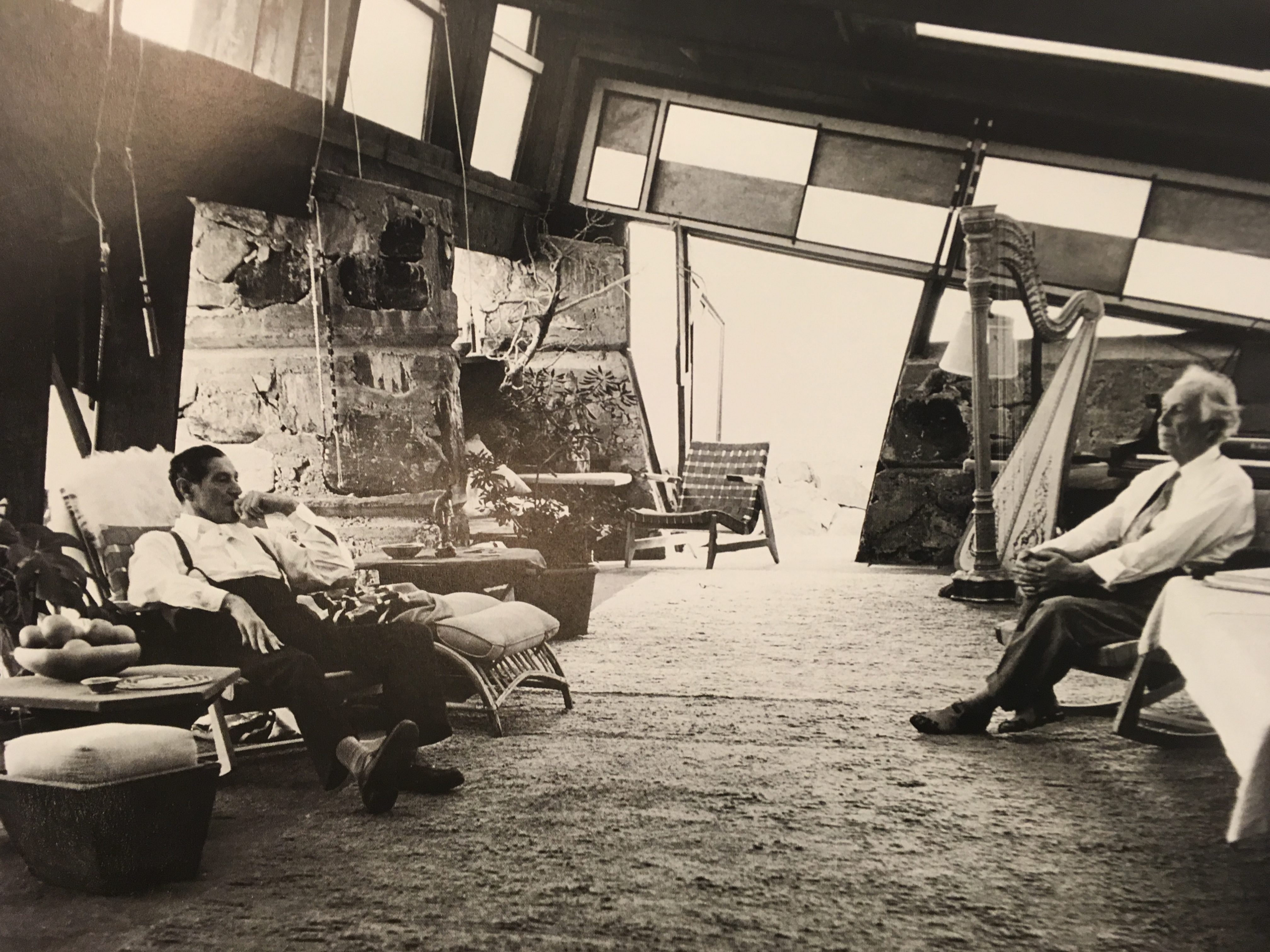

Eddie Jr. read Frank Lloyd Wright’s autobiography and became enamored with the man and his philosophy (ah, yes, the power of books). He moved back to America and enrolled in the Taliesin Fellowship. While working under Wright, Eddie Jr. arranged for his father to meet the great architect. The Kaufmann’s summer cottages outside of Pittsburgh were deteriorating, and Edward Sr. was considering constructing a summer home. Eddie Sr. met Wright and according to students at Taliespin there was “an immediate rapport”:

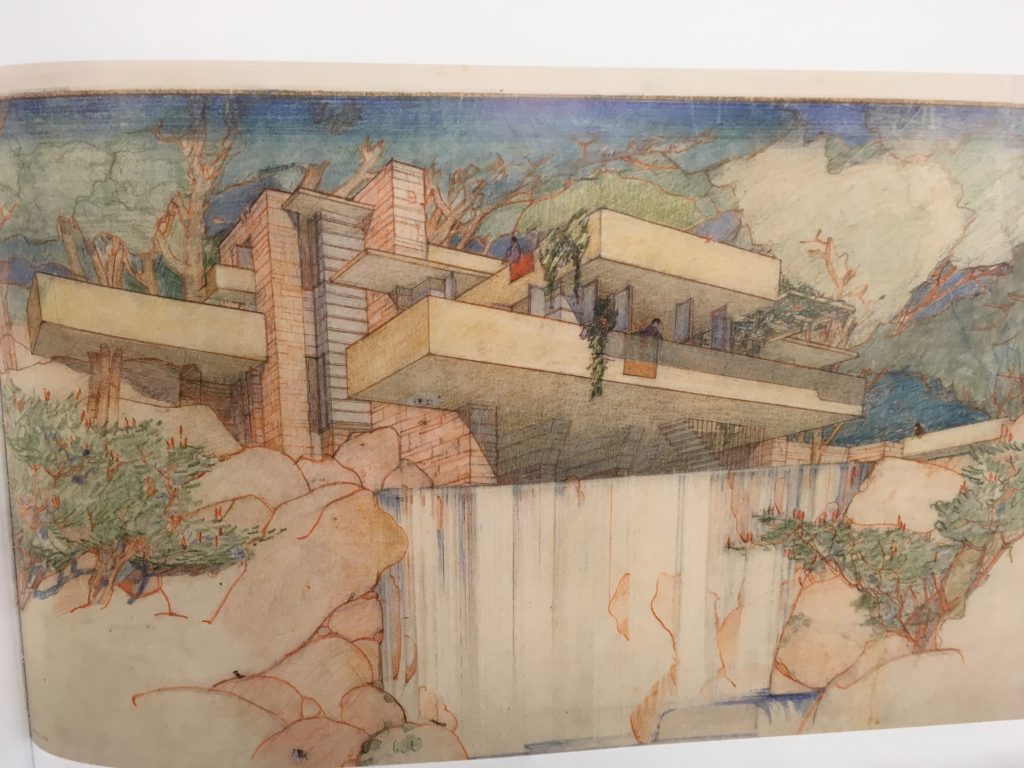

Edward Sr. commissioned Wright to build his summer home, to be located on Bear Run stream and looking at the waterfalls (picture below), 43 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, where the Kaufmanns liked to frolic and bathe:

After Wright visited the site, he wrote to Kaufmann, “The visit to the waterfall in the woods stays with me and a domicile has taken vague shape in my mind to the music of the stream.” But Wright would go against Kaufmann’s initial desire for a location away from the cascade. Wright would build the house on top of the waterfalls: “No, not simply to look at the waterfalls but to live with them…making living space over and above the stream upon several terraces upon which a man who loved the place sincerely, one who liked to listen to the waterfall, might well live.”

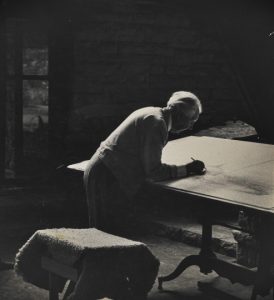

Towards the end of 1934 and the beginning of 1935, Wright visited Bear Run stream numerous times. But he never drew a single sketch of his plan. According to his students at Taliesin, Wright received a call from Kaufmann nine months after their first meeting. Kaufmann would be arriving in two hours to check up on the plans for his house. Oh, shit. Upon hanging up the phone, Wright immediately sat down and drew all of the plans for Falling Water. Yes, like all great procrastinators, he had been letting the ideas marinate and stew:

Construction would start in April of 1936 and be completed in 1938. Throughout construction, there were constant conflicts between Kaufmann Sr. and Wright. Local engineers informed Kaufmann that the “daring cantilevers” would collapse. When Kaufmann confronted Wright about this potential issue, Wright took offense and said: “You are not worthy to have a house of mine if you believe in that junk!” Wright requested Kaufmann return his drawings and that the project be terminated. Kaufmann gave in to the threat, and the engineer’s report was buried in a stone wall of the house. The cantilevers would hold. Sit down Kauf-daddy.

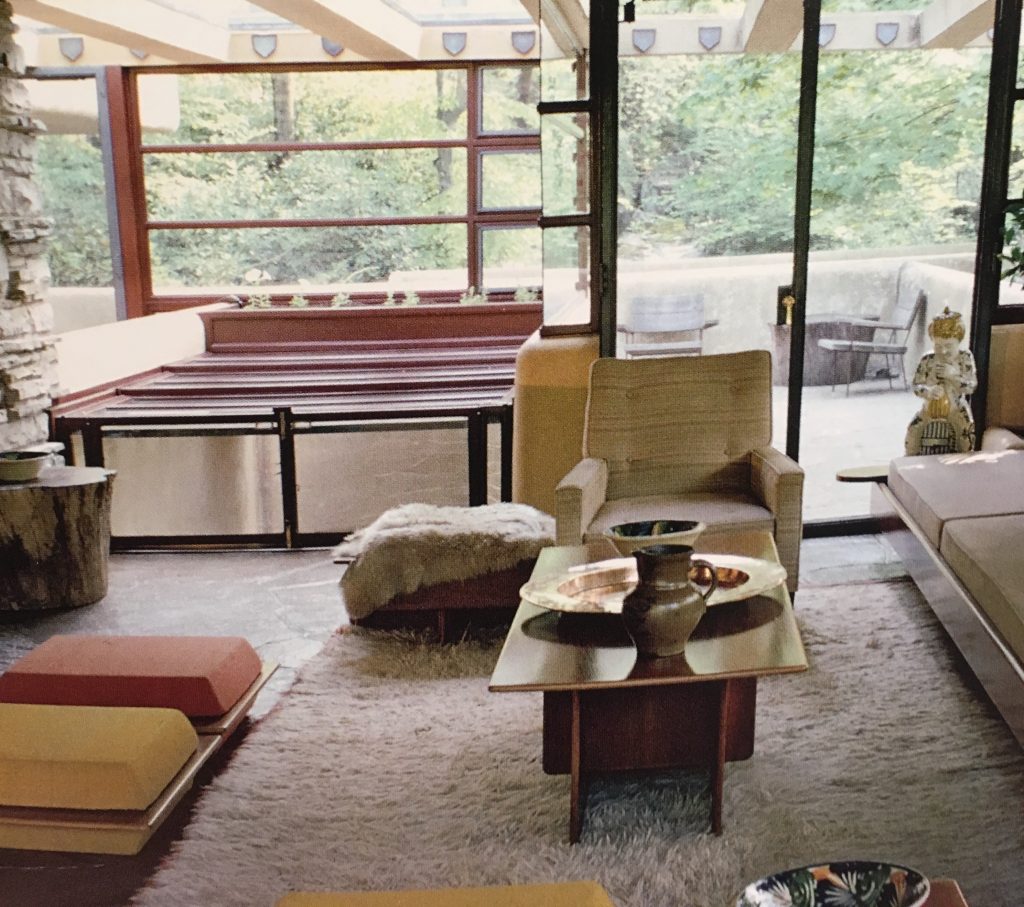

The original cost was supposed to be $613,636 (in 2017 inflation adjusted dollars). The total cost ended up being $2.7 million (2017). Wright believed cost was of little concern when he was creating timeless art. Historians of architecture believe Falling Water was one of the first extravagant-private homes built for someone who wasn’t royalty. Wright also designed all of the interior furniture himself, often using his favorite color: Cherokee Red:

Wright’s passion for Japanese architecture was strongly reflected in the design, with an emphasis on interpenetrating exterior and interior spaces. Five years ago when I visited this house with my father, I felt the contradiction of being in a cozy, protective, bear-den-like place (especially on the main floor with the low ceilings, picture above) yet at the same time always feeling like I was outdoors, as you can hear the stream throughout the entire house, and the windows let in large bursts of sunlight. Also, the windows look out at the middle of trees, so you feel like you’re hovering in space when you look out:

***

Falling Water, the epitome of organic architecture, was a turning point for Wright’s career. He would go on to design the Johnson Wax headquarters, constructed 1936-1939:

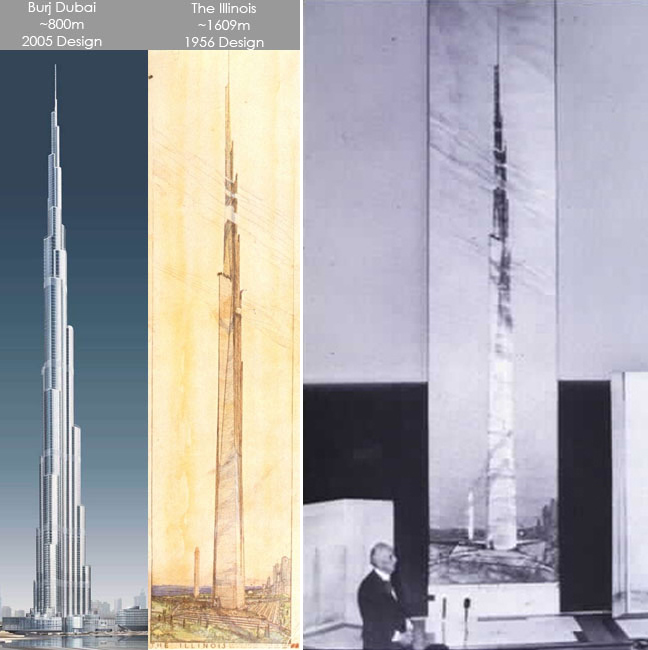

The Price Towner in 1956:

At the age of 88, he would hold a press conference to build a mile-high skyscraper:

And he would design the Guggenheim museum in New York City, which would be completed in 1959, three months after his death at 91:

Throughout the second half of Wright’s revitalized career, he would maintain his arrogance. Look Magazine reported that Wright once identified himself in court as, “The world’s greatest living architect.” When his wife told him he was being ridiculous Wright replied, “You forget…I was under oath.”

Moral: Even if you’re 65 and your career seems to be in the gutter, don’t lose hope, sustain your arrogant belief. There might be 26 years left in you. There might be a waterfall waiting.

Subscribe below: