10 minute read

“I’ll be honest, Vance, this is going to feel like a spike being driven into the back of your skull.”

“Ready.”

“Most patients pass out when the nano-bots are injected. Unfortunately, we can’t give you any sedatives or we’d compromise the installation. Now lean back.”

“Got it…and just to go over what you said before, this hyper algorithm will only be active when I’m wearing my genius glasses, right?”

“Correct.”

“And if I pass out, I’ll wake up within at least ten minutes? Vincent, my son who you met in the waiting room, is participating in a bi-lingual experience at the Paris Brain Institute later this morning and I need to go with him.”

“Don’t worry. You’ll be out of here by eight o’clock. Now close your eyes…try and relax.”

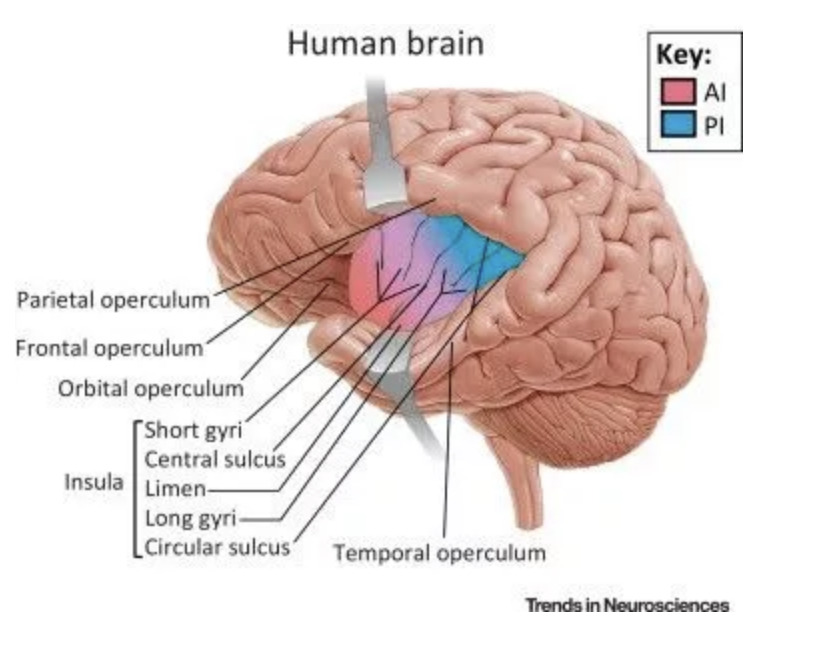

Thirty minutes later, on metro line 7, Vincent and I were jammed between bodies and automated doors (annual summer training strike) on our way to the Paris Brain Institute. Since I hadn’t read the proposal for the experiment thoroughly the night before, and I wanted to test out this new hyper algorithm, I glanced at my left forearm where my genius phone was implanted and scanned the proposal in more detail. Simultaneously I saw my hyper algorithm, customized to my personality and thought patterns, create a pop-up window in my genius glasses next to the text with links to recent developments in neuroscience, correctly measuring and predicting my ignorance and impending curiosity on the subject. Wow. Ignoring this with a flick of my pupil (my genius glasses registering the movement and minimizing the neglected content) I turned back to the proposal and mentally summed up the academic acrobatics: the neuroscientists were going to measure how Vincent’s experience changed, using extremely detailed brain scans, as he spoke and thought in French or English. More specifically, they were going to measure changes during an eight hour window in his insular cortex, an older cortex in the brain that is folded deep within the lateral sulfus, the fissure separating the frontal and temporal lobes. My hyper algorithm seemed to read my thoughts: a pop-window and a picture re-appeared with clarification stating that the insular cortex/insula is where taste occurs, but more importantly it plays a role in visceral and emotional functions.

I returned to the recent developments with another pupil-flick and saw that in the past five years neuroscientists had also proven that the insular cortex represents experience from inside our bodies. In the 2020s, neuroscientists called the prefrontal cortex the seat of consciousness. In the 2030s, scientists confirmed that the insular cortex, a part of the prefrontal cortex, is the existential control panel, an anatomical integration hub with heavy connectivity to other parts of the brain which receives sensory inputs from all modalities.

“Dad, this is our stop right?”

“You got it.” I triple blinked to close the virtual windows as we pried ourselves out of the crush of bodies, crossed the platform, and climbed the stairs.

“Finally,” Vincent raised his arms to the sky. “I can breathe.” We got out at Les Gobelins and walked northeast to the institute.

It was an overcast, boiling hot day, the pavement seeming to sizzle, another summer where Paris was breaking heat records. Vincent didn’t mind the heat since he had grown up in this steadily burning urban hotbox, but I felt the baking waves and dense pollution as if they were cooking my skin and grating my throat. We passed a crumbling statue of a forgotten hero, a family of three picking through trash, and a restaurant with rows of wicker chairs and circular marble tables. Vincent said,

“Dad, I gotta piss like a race horse. Can I stop quick?”

“Sure.”

While Vincent was in the bathroom I continued reading. I learned that other functions of the insular include autonomical and motor control, risk prediction and decision making, and complex social functions like empathy. In the proposal, the researchers wrote, If you see the person you’re in love with, attempt to listen to your own heartbeat, or desire a piece of peanut butter pie, your insular will show increased activity on a brain scan. I wondered how the human insular cortex differed from other animals, and on cue (which was starting to become a little frightening) my hyper algorithm shared a link:

In lissencephalic species, including mice and rats, the insula lies exposed on the lateral surface of the brain above the rhinal fissure, while in human and primate brains the insula (which means “island” in Latin) is folded below the lateral sulcus and is hidden by the opercula. This shows us that the insular cortex is necessary but not sufficient for human consciousness; it cannot create consciousness on its own but consciousness cannot exist without it. I thought about how this current thought would look captured in my brain (a frozen, microscopic-fireworks-finale radiating throughout my skull?) Then I thought about how nature is overflowing with accidents on the treacherous path of evolution, but that it was unlikely a coincidence that as rodents evolved into apes, then humans, this essential part of consciousness would be tucked and hidden deeper inside the thinking apparatus if it wasn’t crucial to reality construction and manipulation. I felt a tickle in my left forearm, a sensation reserved for messages from family and close friends:

“Dad, not pissing, dumping. Will be out in a min.”

“Thanks for the update.” I continued reading.

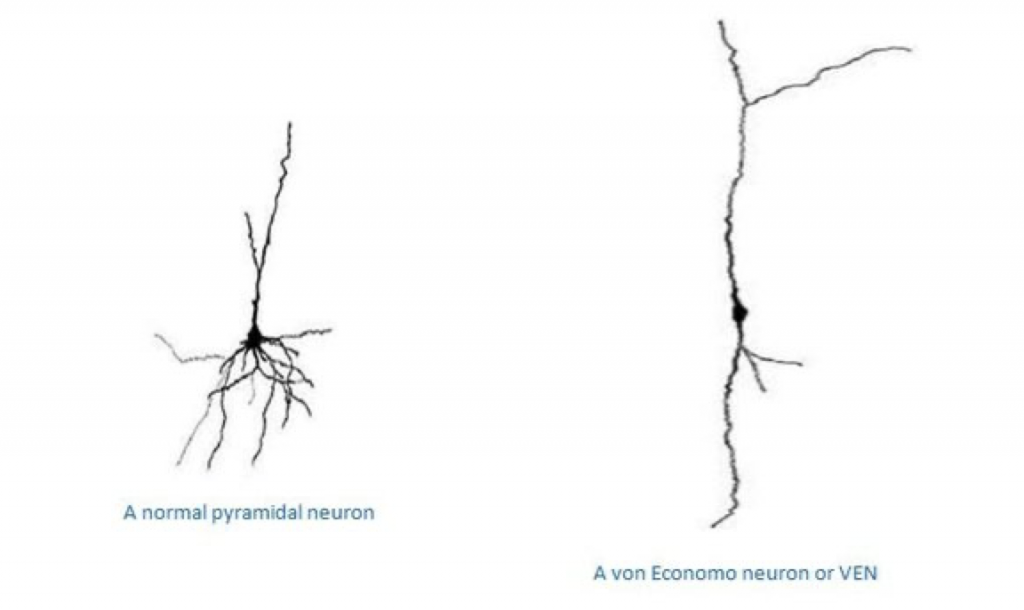

A unique characteristic of the insular cortex in humans (and whales, elephants, and great apes) is the presence of a special cell type called “von Economo neurons” first formally described by Constantin von Economo in the 1920s.

For over a century the exact function of this cell type was not known. Neuroscientists had only observed that these special cells, also known as spindle neurons, were selectively destroyed during frontotemporal dementia and were unique to animals with large brains and advanced socialization skills. The average human has about 82,000 such cells, a gorilla 16,000, and a bonobo 2,000. Whales have around 240,000. The large quantity of spindle neurons in whales shouldn’t be a surprise when we learn that whales communicate through massive song repertoires, recognizing their own songs and making up new ones, forming coalitions to plan hunting strategies, teaching these strategies to younger individuals, and creating evolved social networks. They also have 15 lb. brains, so the neural transport routes the spindle neuron has to travel to reach other parts of the brain are longer (average human size = about 3 lbs.). While initially neuroscientists believed that these spindle neurons were the foundations of sophisticated social behavior (orcas have complex social hierarchies with females at the top) more recent developments have shown how they also play an integral part in our conscious awareness of reality. Neuroscientists have acknowledged that you cannot separate social development, whatever species you are, from an understanding of your self, time, and space. Humans who have been in solitary confinement for long periods of time not only lose their social skills, they often lose their sense of self and their surroundings: their brains degrade as they experience memory loss, cell death in the hippocampus, overall cognitive decline, and depression.

Justification for the importance of spindle neurons in consciousness was found in 2028 in a study on schizophrenics. In 2016 it was shown that subjects with early onset schizophrenia (and a longer duration of the illness) had a reduced spindle neuron density. In 2028 post-mortem analysis of brains of schizophrenics was able to show how the degree of delusions experienced by the subjects (measured before their deaths by interviews recording the self-reported quantity of imaginary voices/people experienced by the subject) related directly with the degree of degradation of their VENs (von economo neurons). VENs provide rapid transmission of information to other parts of the brain, and if these neurons can’t do their jobs we begin losing our grip on what’s real or not. I wondered if a future human would ever “evolve” a neuron more sophisticated than these spindle neurons and how this new neuron would alter behavior or the reality experienced. Then I refocused on the proposal and saw that the Paris Brain institute was going to analyze the activity of VENs in Vincent’s brain.

“I’m back!” Vincent came running out of the restaurant. “Didn’t know I had to drop the kids off at the pool.”

“I had a feeling you would.”

“How?”

“I follow your eating habits and we share similar digestive tracts.”

“Right.”

The Paris brain institute is in a U-shaped building that has floor to ceiling black windows wrapping around the exterior. Built in 2010, it is a modern architectural island amongst rows of decaying yellow brick buildings. The structure (I snapped a picture with my genius glasses) resembles a giant, glass magnet.

We crossed a wooden bridge, pushed through the glass doors, and were greeted by stern-faced security guards. After giving us the “once-over” one of them said,

“Bi-lingual experiment?”

“Yes.”

“Leave an I.D. at the front desk and follow me.”

We passed a piece of artwork, a marble circle with a piece missing (I snapped another picture), were led down a nondescript corridor, then entered a cavernous auditorium.

Parents and their teenagers were already sitting in cushioned seats, reading and poking tablets.

“Welcome, Bonjour, Vincent and Vance.” A young man with wispy, parted hair and eyes framed by round glasses approached us. Vincent turned to me.

“How does this guy know who we are?”

“I’m informed by security each time a new participant arrives.” He gestured to a genius implant in his left forearm, which was blinking with a message: arrival of new participants. “My name is Sigmundus Vetus. Pleasure to meet you both.”

The man made me uneasy. But we shook hands anyway and I let him hand us two tablets.

“The parent fills out the release form, the child a quick survey. I’m sure you know the drill.” I didn’t, but again I nodded and took the tablets.

We sat in two seats away from the others and started filling out the forms, clicking boxes and signing our names with our index fingers. My form only took thirty seconds, basically saying that I wouldn’t engage in legal action if anything went awry. I ignored the twenty pages of fine print, and was about to return to my research stemming from the proposal when Vincent nudged my shoulder.

“You should really read the fine print, dad.”

“Why’s that? If they kidnap you or cut your brain out, it’ll be for the glory of science.” My generation had grown up ignoring “terms of agreement” and fine print supplements. Vincent had been warned against this, probably from teachers. He smiled, but his voice was firm.

“No joke. It’s the same idea as that hybrid algorithm you just bought. You should really read the fine print on those things. New technology can be dangerous. Especially when your mind spent decades without it.” I faked a robotic, monotone voice, staring blankly into the distance.

“Warning…of…imminent…malfunction.”

“I’m serious. I read the fine print on your hyper algorithm and there’s been reported incidents of the technology comprising other implants.”

“Appreciate you looking out for me. I’ll be careful. But I need this algorithm for work. The firm paid for half of it so I could finish a contract I’m working on before a deadline.”

“Yeah but will they pay for permanent neural damage?”

“Probably not. But I take risks so you can live your pampered life of luxury.”

Vincent shrugged and continued filling out his survey, and I looked over his shoulder at the questions. They were fairly “establishing a psychological baseline basic,” asking about diet, screen time, how many books he reads per week, how much sleep he gets, exercise, and emotional variability. I double blinked and looked back at the proposal description:

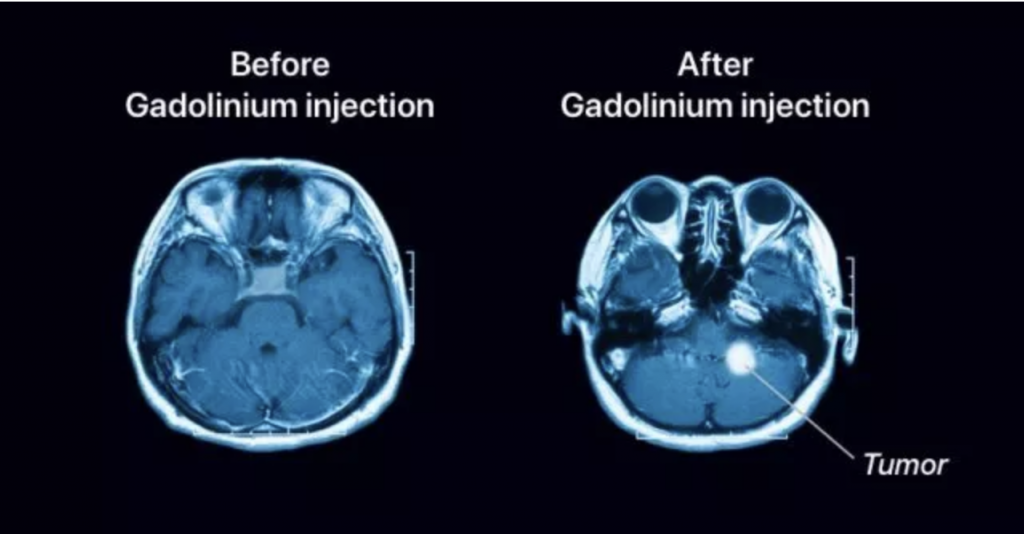

Before the observational period would begin the participants were going to be injected with a contrast material, gandolinium, a rare earth metal that when present in the body alters the magnetic properties of nearby water molecules. (Is that why the building is shaped like a magnet, an architectural wink to M.R.I. machines?)

Gandolinium improves the quality of the brain scan through enhancing the sensitivity and specificity of the images.

In the early 2020s, when subjects received brain scans, they would have to lie in a big M.R.I machine, remaining still for +30 minutes, while a machine hummed and buzzed. (I remembered lying in one numerous times as a teenager for the 4 stress fractures I developed in my tibias from running a lot). Now the technology had progressed to the point where subjects just had to wear a bulky helmet, a mobile upgraded “head coil.” This allowed the neuroscientists to create more realistic environments and get more accurate results. Another breakthrough in neuroscience in the past five years was recognizing the importance of mobility in brain analysis and development. The participants in this study would be moving about and tasting various foods while either speaking (and thinking) in French or English. A giant machine, likely hidden in the ceiling, would be sending and receiving waves, uploading the brain scans to a quantum computer.

When I read this part of the proposal, the fireside science critic in me immediately raised a red flag: how could these neuroscientists think that they could separate language’s impact on experience from culture’s impact? Isn’t language inextricably entwined with the cultural traditions, values, and history in which it was born and developed? Of course Vincent would experience more brain activity while thinking in French and tasting than in English, French culture is a food culture, valuing culinary experiences (in general) more highly than English speaking cultures (have you ever tried English cooking/eaten out of a dumpster?) In the past two years I’d heard Vincent have 30-60 minute conversations with his friends about food (how it was prepared, how it compared to other dishes, how it could be improved, etc.) Even though English has 6x more words than French (600,000 vs. 100,000) French has more ways to describe taste and food than any other language. (The French language’s 100,000 words has 350,000 meanings). What does culture’s impact on our identities look like in the brain?

My hyper algorithm must have been measuring how long I was stuck on a sentence, and sensed my doubt and reflection, because the machine infiltrated the proposal (how did it do this?) and scrolled down to the bottom where the neuroscientists had already responded to potential criticisms.

We acknowledge the cultural influence on language and the challenge of separating a language’s influence on reality from the culture’s influence. We do not believe this undermines the purpose of our research nor the results.

Right.

When Vincent finished filling out the form he was called into another room with the other participants.

“See ya, dad.”

“See ya, son.” Vincent looked off into the distance, mimicking me when I did the robot voice.

“Humanity will never be the same again once they have learned what’s happening inside this brain.”

“God help us. Go get your pay check.” He smiled and left. Five minutes later Sigmundus Vetus returned to the auditorium to address the remaining parents, friends, or guardians.

“If any of you would like to observe the beginning of the experiment, please follow me.” A few of us followed the doctor out of the room, up some stairs, then into a chamber with floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the bi-lingual subjects. I saw Vincent being shown how to put the M.R.I. head coil on his head by a nurse while another nurse put a needle in his arm (injecting the gandolinium, I assumed). For the next ten minutes I heard Vincent and the other participants being told directions, speaking French, being offered various foods, and being observed by doctors. My hyper algorithm blinked a reminder on the edge of my vision: work. I left and went to the office.

About 7 hours later I was back at the Paris Brain Institute to pick Vincent up. In the auditorium the lights were dim and Sigmundus Vetus was on the verge of an announcement. Vincent was sitting in the back row and motioned me over to a seat.

“How’d it go?” I asked.

“Boring, but check it out.” Vincent showed me his phone with a payment accepted from the Paris Brain Institute enlarged: $680.

“Good. Now you can start buying toilet paper.”

“Do we have to stay for this?”

“No, let’s get out of here. Mom made a quiche.”

On the 7 line back home I thought about the experiment and told myself that I would follow up on the results. Vincent was reading a book. There was more space in the metro, we weren’t packed like sardines, but there still weren’t any seats available and we were standing in front of the doors.

I’ve always believed that movement and activity stimulates and accelerates the formation of ideas. For months I had been stuck on an engineering problem at work, holed up in my office, surviving on coffee and croissants. But after going out with Vincent and being on the periphery of new research, of witnessing humanity pushing the boundaries of our understanding firsthand, something in my brain started to turn. Vincent looked up and smiled. I felt an idea begin to take shape, its contours and attributes becoming gradually clearer, like a sunrise over a rocky landscape. The answer to a structural problem appeared in my mind’s eye. The answer and path to get there was raw, uneven, and jumbled, it would still need work and tweaking, but at least I knew which direction to go, which step to take, and-

My visual field seemed to explode. I felt an excruciating pain in my left wrist, a constricting sensation in my genius implant. My hyper algorithm was filling my genius glasses with thousands of pop-windows, links, video clips, recommendations, warnings, graphs, an avalanche of images. My retinas burned, my right ankle, which was loaded with nano bots all connected to my hybrid algorithm via a health monitor, crumpled. All of this happened in a spilt second, the malfunction causing me to seize up as if having an epileptic seizure. My legs buckled, I started to fall, then I felt an arm encircle my lower back, preventing my head from smashing the metro floor.

Vincent had somehow caught me mid-fall, taken off the genius glasses with a deft swipe, then easily lifted me back up to a standing position. The travelers around us stared at Vincent in awe. An old man with a dog even chuckled and clapped. Vincent turned the genius glasses over in his hand.

“I knew that hyper algorithm was fricking dangerous.” I was still getting a grip on what had just happened, waiting for my implants to return to baseline, processing the previous five seconds. Before I could say anything, Vincent looked up.

“You had an idea. Didn’t you? That’s why your hyper algorithm went bezerk. It knew you were on the edge of something.”

“What? That’s…how did you know?”

“C’mon dad, I can see it in your face ten seconds out.”

Subscribe below: