According to Mary Meeker’s annual Internet Trends report, in 2014 people uploaded an average of 1.8 billion digital images every single day. To put this in perspective, every two minutes humans took more photos than existed in total 150 years prior. GOD DAMN. No doubt this number has increased substantially in 2018…as more people have phones with cameras and meals that must be posted on Instagram. With such quantity, such instantaneous feedback, and such convenience, has the quality of photographs improved or suffered? What are the ingredients of a quality photograph? Perhaps the clarity and shock-value of particular photographs have improved, but has something subtle been lost when you don’t have to stay up all night developing a photograph in a dark room, but instead can press a few buttons and upload the image on to social media? Does the search for meaningful subjects become compromised when you can instantaneously capture and develop/add a filter to an image? How much can someone’s character be judged by the photographs they choose to take? I don’t know. But by looking at the past work of Margaret Bourke-White, a photojournalist between 1925-1960, answers to these questions may be reached. Because Bourke-White was, interestingly, both a first and a last artist, meaning one of the first photojournalists to make a career out of taking photos, but also one of the last journalists who had risen to success through the old fashioned way of photography. Whether she created timeless art is for you to judge. But her art aside, she was also a powerful woman who lived on the edge…here is her life:

Margaret Bourke-White was born on June 14th, 1904. As a child she showed a sense of adventure and a curiosity for life, as one summer she raised two hundred caterpillars under rows of upside-down glasses on a dining room windowsill.

She was very close with her father, Joseph White. He’d take her on walks outdoors, teaching her how to decipher between harmless and dangerous snakes, and how to pick them up without fear. With her father’s introduction to the world of snakes, Margaret decided to become a herpetologist. Her motivation to study snakes was fueled by a desire to travel and a desire to do “things that women never do,” (MBW, 14). Her father encouraged her herpetology by constructing wire cages to house her growing collection of snakes and turtles. Margaret would major in herpetology when she enrolled at Columbia University at the age of seventeen.

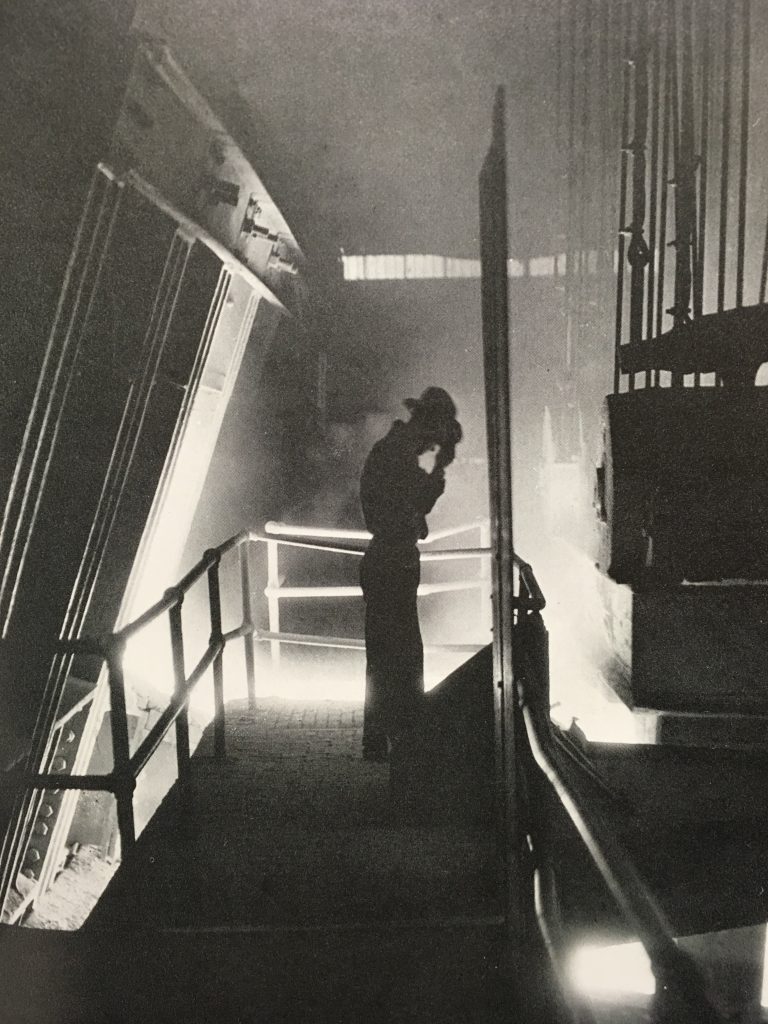

Joseph White was an amateur, though passionate, photographer. He was a stern, silent man who was not to be disturbed in the house while he was “thinking.” Joseph was an inventor who worked with printing presses, earning numerous patents such as the first printing press for Braille. During his life he would dedicate his “heart and mind to a tangled love affair with the rotary press,” but due to failed investments would never become wealthy (G, 101). He was, “Always tinkering with lenses and working on devices to make exposure settings simpler for the amateur [photographer]…” (MBW, 20). He would take Margaret on trips to factories where he was supervising the setting up of presses. On one of these trips, Margaret witnessed the flowing of metal and flying sparks in a foundry, and would write about the experience later in life: “To me at that age, a foundry represented the beginning and end of all beauty.”

Her father instilled in her a love for industry and work. On industry, Margaret would write:

“Ore boats, bridges, cranes, engines – all are giant creatures with steel hearts. They all have an unconscious beauty that is dynamic, because they are designed for a purpose. There is nothing wasted, nothing superficial. The realization of this idea will grow. It reflects the modern spirit of the world,” (G, 112).

And on her father instilling a work ethic, Margaret would write:

“His [Joseph White] positive contribution was to build in me the deepest respect for work. Work is a religion to me, the only religion I have. Work is something you can count on, a trusted, life-long friend who never deserts you.”

While a freshman at Columbia University in 1921, Margaret’s mother bought her a camera, a 3¼ x 4¼ Ica Reflex. It cost $20 and had a crack in the lens. At Columbia, even though she majored in herpetology, Margaret would also study art. She’d hear a lecture by the artist Arthur Wesley Dow, who was teaching at Columbia University Teachers College, and would later use his Orientalizing design principles in her photographs of gardens and estates in Cleveland (G, 68). In addition, the teachings of Arthur Wesley Dow grounded her thoroughly in the potential of abstraction from realistic observation (G, 111).

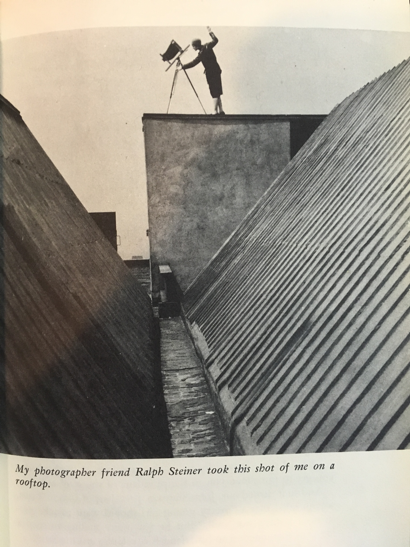

Then, by lucky chance (according to Margaret) she took a two-hours-a-week course in photography under the late Clarence H. White, “…not because I wanted to take photographs but because the course dealt with design and composition as applied to photography.” But in her notes later in life she also reflected, “I think my great love for my father and the fact that he was so much interested in photography was a strong added incentive when I began work at the Clarence H. White School,” (G, 24).

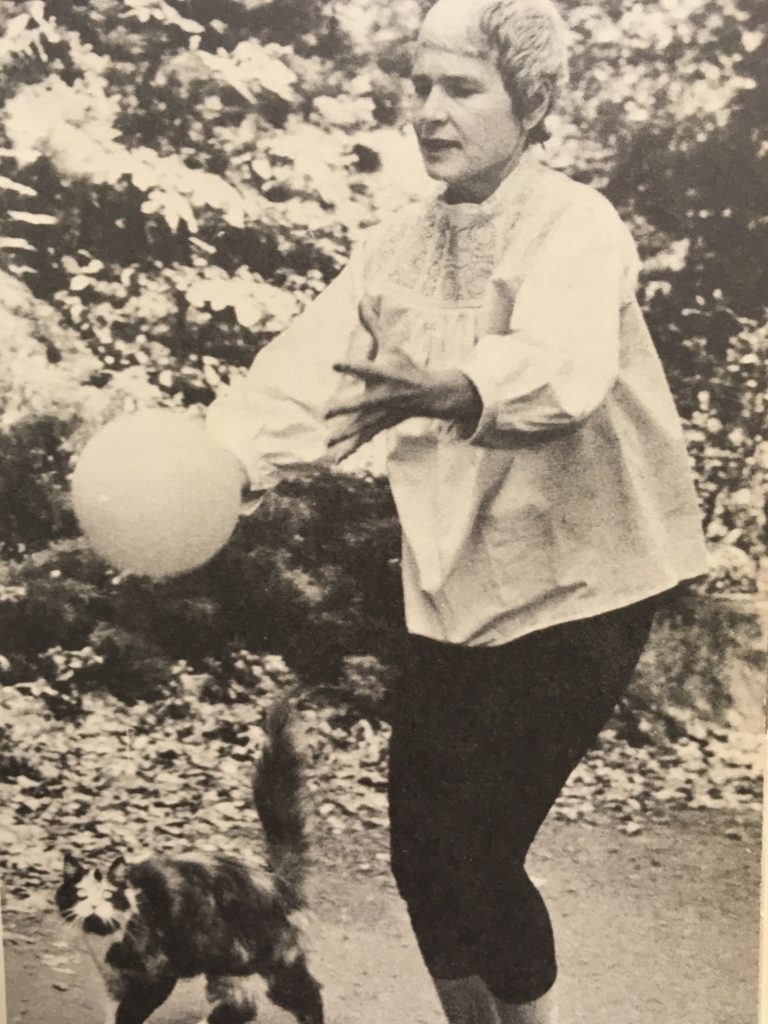

Margaret wrote in her autobiography that, “…Clarence H. White was a great teacher and the [photography] seed was planted.” One of her classmates, Ralph Steiner, would become a colleague for life, giving her technical advice on photography over the years. In their first class together, Ralph said Margaret had, “Terrible, intense, staring eyes that didn’t blink,” like the cold-bloodied animals she studied. When Margaret would study at Cornell, she would describe Steiner as a “superbly sharp honest craftsman,” who “caustically talked me into a fierce reversal of the viewpoint that a photograph should imitate a painting,” (MBW, 30). He would take photos of Margaret later in life:

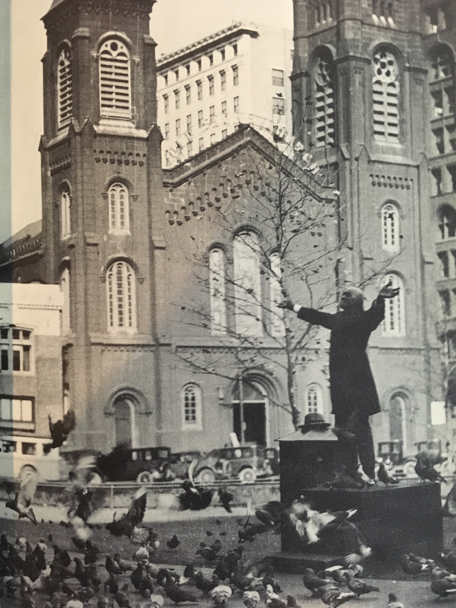

After a disastrous marriage and attending numerous universities after Columbia University, Margaret would move to Cleveland into a tiny apartment by herself. She’d develop films in her kitchen sink, rinsing them in the bathtub. The first photograph she would sell commercially would be a picture of preacher and pigeons, which she sold to the magazine of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce for ten dollars:

In 1927, Margaret was constantly visiting industrial sites, saying, “I can’t describe the feeling of rapture and real ecstasy that I had when I got to all that industrial activity,” (G, 74). The majority of her photographs around this time concentrated on dynamism, movement, construction, process, teeming steel, the pouring of metal, and coke being quenched. She began to realize the democratic power of photographs, as, “Even in its most complex combinations, anyone can understand most photographs.”

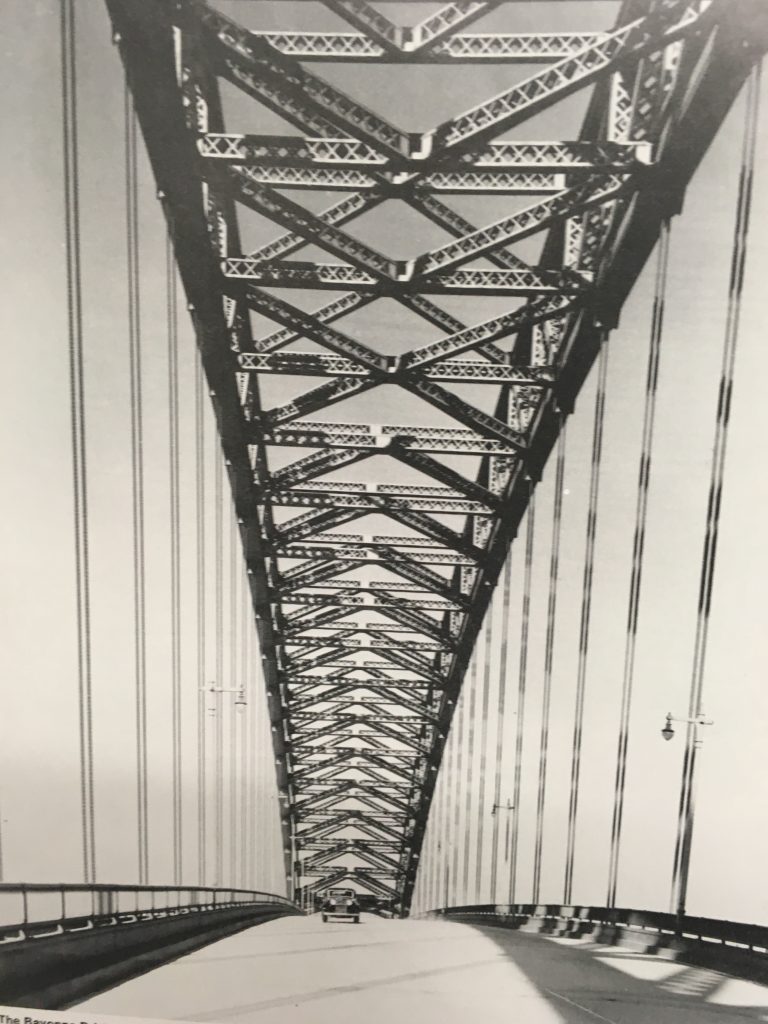

The same year a friend of Margaret’s suggested that she bring her industrial pictures to the Union Trust Company. The Union Trust Company was desperate for covers for their monthly magazine called Trade Winds. After they saw Margaret’s portfolio, they agreed to give her $50 for its cover, a picture of the High Level Bridge. They would continue with this monthly payment contract for the next five years. As Margaret began to receive more money for her work, her certainty in her path grew:

“…I didn’t know exactly what direction I was headed except that it was upward. I didn’t know exactly what my goal was. I didn’t see a fixed goal but I knew that I was progressing and that I would succeed,” (G, 78).

In 1927 American industry was reaching a peak of profits and productivity. The respect for business was reaching a kind of national reverence. The time was ripe for someone like Margaret to inform the capitalist that in the means of production lay the sparks of high art. Between 1921-1929, industrial production in the United States nearly doubled. President Calvin Coolidge would say, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple, the man who works there worships there.” And Henry Ford believed that “machinery is the new Messiah.” Margaret’s timing was perfect, and her pictures of dynamo in the Niagara Falls Power Plan in 1928, taken for the state set of Eugen O’Neill’s Dynamo, earned Margaret the reputation of “The girl who discovered the dynamo,” (G, 81).

But her breakthrough would come when she went to the Otis Steel plant to take photographs. When she arrived, the pouring of the metal gave off more heat than light, and Margaret would end up improvising with flares to achieve better lighting. In addition, a few days after she started work, a corporate publicist named John Hill wrote, “I had a call from the night superintendent of the mill. He demanded that I keep ‘that girl out of the plant,’ he said. ‘She’s crawling all over the place, and the men are stumbling around gawking at her. Someone is going to get hurt, and besides, they’re not getting any work done.’” Margaret replied, “I’ll wear blue jeans,” and returned to the mill. This would be one of many examples of Margaret experiencing backlash in a male dominated industry. The picture of the mill’s two hundred-ton ladle would win her the first prize at the Cleveland Museum of Art show in May of 1928. She would later write, “I feel that my experimental work at Otis Steel was more important to me than any other single thing in my photographic development.”

Work was becoming the main focus of her life. She would write Nikolai Sokoloff, one of her many lovers:

“You have never seen me at work. You cannot know how my work has been all of me, and how unwilling I have been to let anything outside of my work seem important to me – Everyone here knows how independent I am and how unapproachable I am. I made up my mind that I would not allow myself to get fond of anyone until I am over thirty. I shall abide by that, because nothing is so important to me just now as to do something in pictures in black and white with the romance and beauty of industry that has never been done before…I have made up mind quite definitely that I cannot fall in love with anyone until I am thirty…” (G, 90).

Even though Margaret was not the first woman to take industrial photographs, she was the first woman who was commercially successful in the field. She was a pioneer for bringing the image of industry to the attention of the American public and giving it a glamour and power it had not had before (G, 90).

In early 1929, Henry Luce saw her Otis Steel pictures in the rotogravure section of a mid-western newspaper. He sent a cable to Margaret which read:

“HAROLD WENGLER HAS SHOWN ME YOUR PHOTOGRAPHS STOP WOULD LIKE TO SEE YOU STOP COULD YOU COME TO NEW YORK WITHIN A WEEK AT OUR EXPENSE PLEASE TELEGRAPH WHEN – HENRY R LUCE PUBLISHER TIME THE WEEKLY NEWS MAGAZINE.” Margaret raced to New York to meet him.

Henry Luce told her that he wanted her to be the first photographer for Fortune (which had initially been planned to be called Power), his new magazine. In the magazine “pictures and words should be conscious partners,” and “the camera would act as interpreter.” He wanted the magazine to have “the most dramatic photographs of industry that had ever ben taken.”

Luce knew that his magazine Fortune and eventually his other magazine, Life, were new means of communication and would change the very nature of reporting. In the past, a magazine would write a story, then a staff would look through an index of important images. Now, the magazine often had the story written, not before, but after the photographs came in (G, 109).

Fortune’s popular appeal was its illustrations, and Bourke-White was the force behind this appeal. She would make industry a theatre (G, 110). In addition, Fortune would feature pictures of politicians caught in mid-gesture, or of statesmen seen through half-opened doors, and these un-posed photographs were revolutionary. The public had never seen this new form before and it was a breakthrough for the press (G, 110).

Throughout this revolution, Margaret was on the center stage. And being a woman enhanced the spotlight. Margaret didn’t play the game the way that women were expected to, with a “sweet and retiring demeanor,” (G, 150). Her famous, often repeated line was, “Nothing attracts me like a closed door. I cannot let my camera rest until I have pried it open, and I wanted to be first,” (G, 125). When asked why she was often single, Margaret would reply, “I don’t need someone else to cling to and I don’t have the need of security that a lot of women do. First of all, not financial security, but even more important, emotional security,” (G, 321). A man told her once she had a lens for a heart. She took it as a compliment and happily repeated it (G, 273).

In 1936 Henry Luce received a telegram from Archibald MacLeish:

“The great revolutions of journalism are not revolutions in public opinion, but revolutions in the way in which public opinion is formed. The greatest of these, a revolution greater even than the revolution of the printing press…is the revolution of the camera…The camera shall take its place as the greatest and by all measurements the most convincing reporter of contemporary life,” (G, 172).

Today, as photographs are so integrated into our daily lives and culture, it’s difficult to comprehend the revolution of photographs becoming a part of the news.

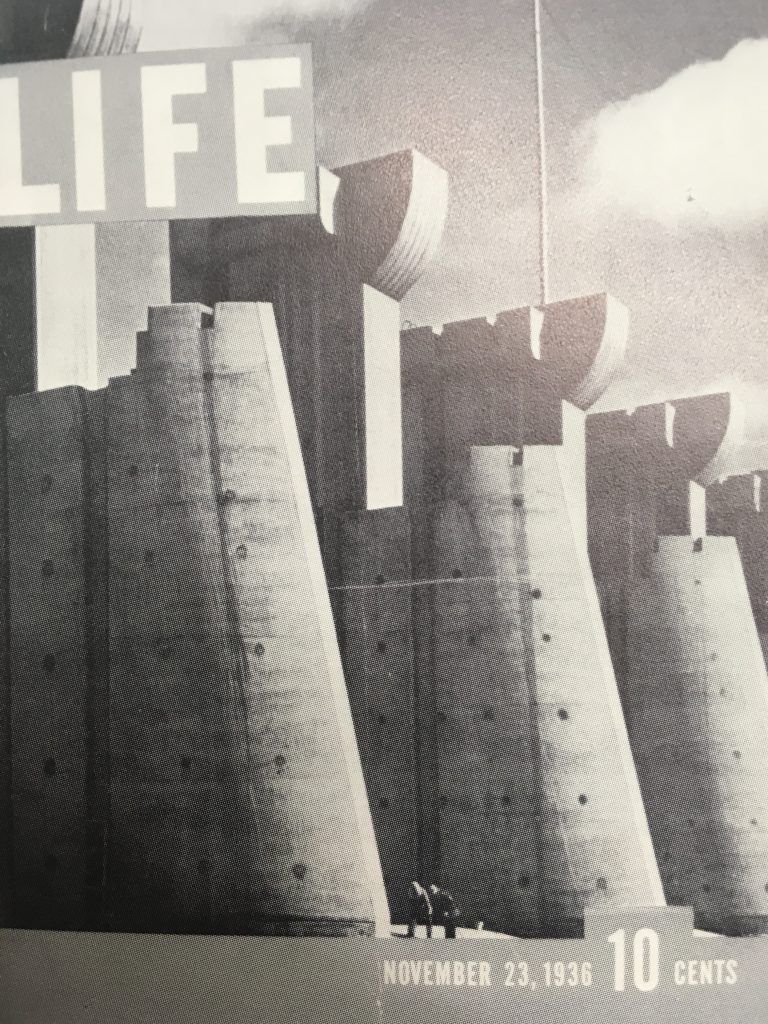

In 1936, Luce decided the world needed a picture magazine, and came up with the idea for Life magazine. He wrote in the first draft of the prospectus: “We have got to educate people to take pictures seriously, and to respect pictures as they do not now do…While people love pictures, they do not respect them,” (G, 174). He hired Margaret two months before publication. Margaret was the only woman and the only big-camera photographer for Life. Her first assignment was the chain of dams that the Public Works Administration was constructing in the Columbia River Basin to control flooding, which would go on the cover of the first issue.

Before Life, no other illustrated periodicals in the world gave the news (or any other kind of story) principally and coherently in photographs. In Life Margaret would pioneer the picture essay, as in the first issue the lead story was about what normal, useful, pleasant behavior was like out West, which was the first true photographic essay in America, (G, 181). Margaret would say, “One of the things I really care about is being given credit for having this essay style,” (G, 180).

In comparing Life to new forms of media and news today, it’s interesting to note that Life didn’t turn a profit until 1939, three years after the first issue. And, the editor at Life had to teach his staff to read pictures, with captions at first being written to help teach the public how to read evidence. People were concerned that the picture magazine would kill off reading.

But reading was not killed off, and photos in Life were seen as the great equalizer, as an ad in Life in December of 1936 wrote:

“The appeal of pictures is universal…the cook and taxi-driver, then may find something in LIFE as interesting as you do,” (G, 183).

Henry Luce saw photography as a kind of remedy for the disheartening effects of the news. In 1952, Life reminded its readers that, “Back in 1937…Henry R. Luce…predicted that photography could be useful in correcting that really inherent evil of journalism which is its imbalance between the good news and bad,” (G, 187).

While working for Life, Margaret would engage in other projects, such as the collaborative book, You Have Seen Their Faces, with her famous novelist husband: Erskine Caldwell. The book, a 1937 report on sharecropping and an indictment of the practice, would influence the country’s legislation and establish a new genre: a book in which photographs and text have equal weight. A New York Times reviewer of the book wrote, “The pictures produce such as an effect, indeed, that it is no exaggeration to say that the text serves principally to illustrate them,” (G, 194).

*

Margaret Bourke-White’s life, as she rode on top of the wave of photojournalism and the first successful photographic magazines in the United States, would be full of adventure. She captured the Dust Bowl, the Soviet Union’s five year plan, she was the only photographer who captured Stalin smiling, she was in a submarine in the Mediterranean that was torpedoed and had to abandon ship, she went on a bombing mission attack on Tunis as the first woman to accompany a U.S. Air Force on a combat mission, she would be in Moscow during the bombing in July of 1942…

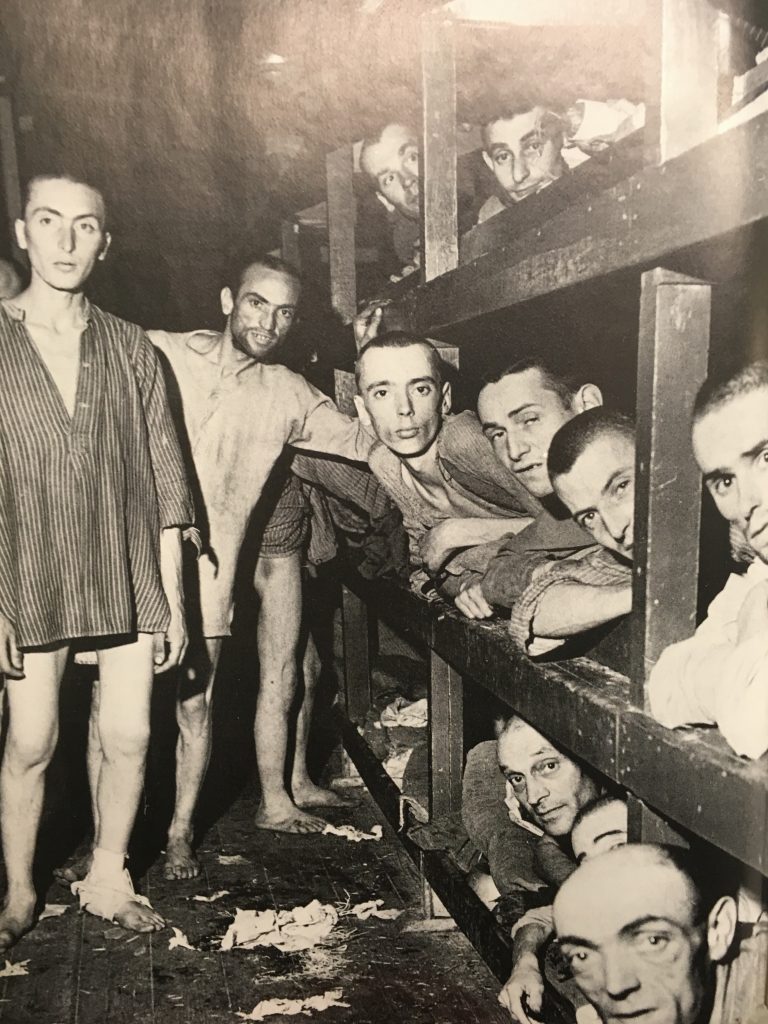

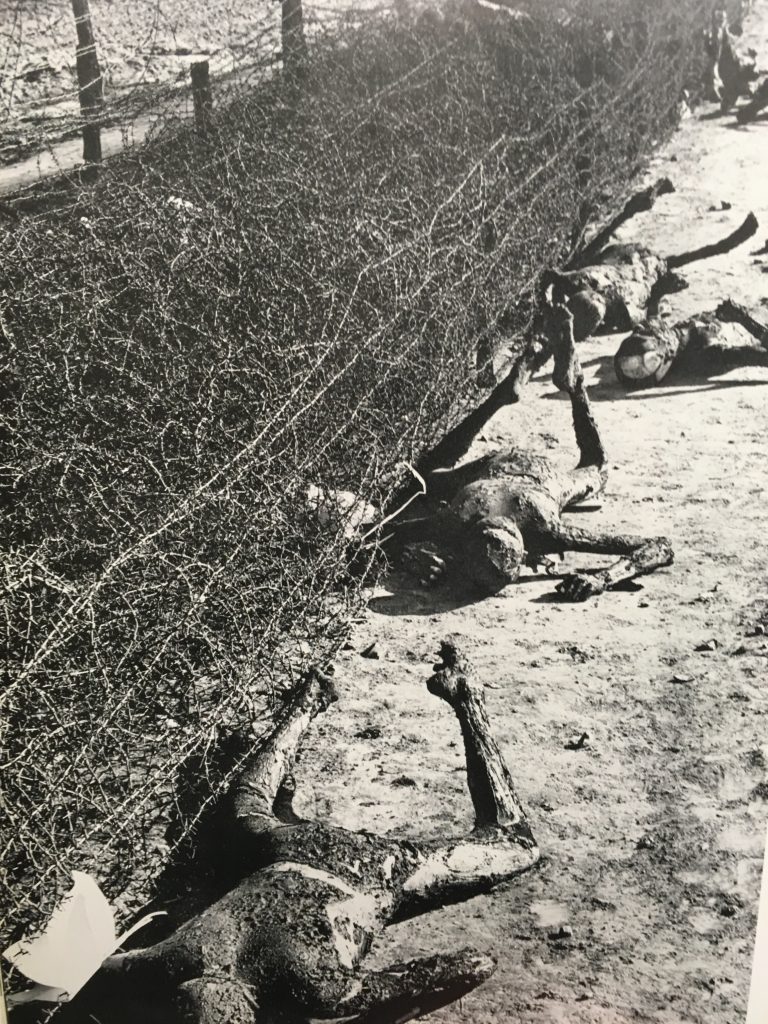

…she flew with Hamp Atkinson and Paul Tibbetts (Tibbets would, two years later, drop the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima), she liberated Buchenwald concentration camp…

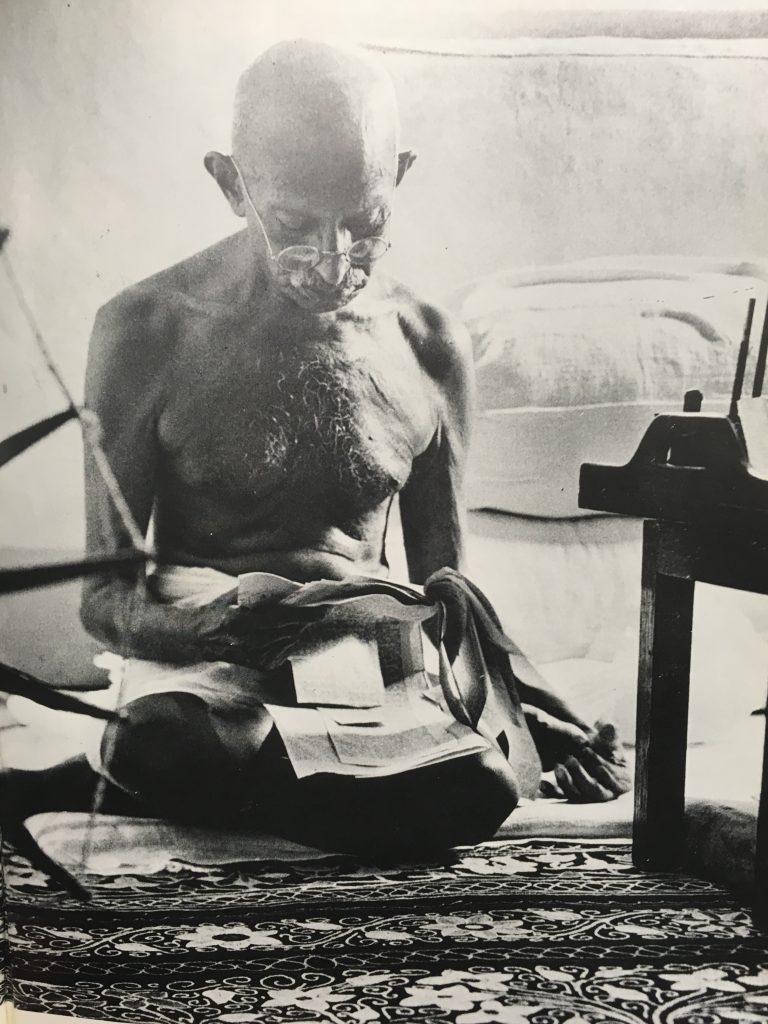

…she photographed the iconic image of Mahatma Gandhi sitting behind his spinning wheel…

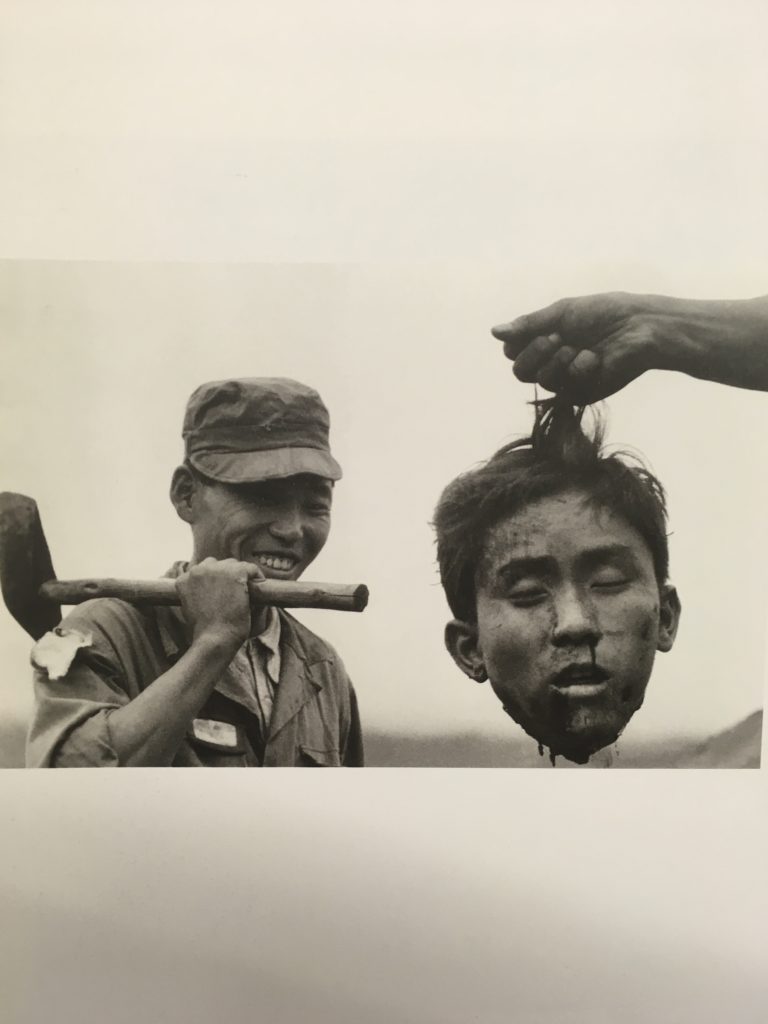

…then interviewed him the day he was assassinated, and she covered the Korean War.

So it seems a cruel twist of fate that a life of such action would be crippled by Parkinson’s Disease in the last eighteen years of her life. As Margaret developed Parkinson’s (she wouldn’t tell friends or co-workers for years after showing symptoms), she would say to a friend, “I feel like a prison in my own self,” (G, 343). She would write, “Parkinsonism is a strange malady…it works into all paths of life, into all that is graceful and human and outgiving in our lives, and poisons it all.” But despite the inner torment, Margaret never claimed that life had treated her unfairly, as her friend Jack Hofkosh noted, “She never asked the one question everyone asks without fail: “Why me?’ The question forced itself on her mind, but she adamantly refused to give it space,” (G, 351).

In fact, in 1955, two years after experiencing Parkinson symptoms, Margaret asked Henry Luce to promise her the assignment for the first trip to the moon. Luce gave her his blessing (G, 347). To the end, Margaret loved life and adventure, overcoming obstacles in stride, even when they seemed unexplainable, as she would write near the end of the life:

“…from whence come the trials by fire. Seems so purposeless, so underserved. Undeserved is something we cannot judge and the very word had to be exiled outside of our consciousness or we could waste what little life we have ahead by complaining that we don’t deserve such fate.” (G, 351).

Subscribe below: