Special thanks to Roy Tomizawa

(Check out his great blog: The Olympians)

And Ichiro Aoyama’s book on Tsuburaya for the

Biographical and historical content.

“If you get nothing better out of the world, get a good dinner out of it.”

-Herman Melville

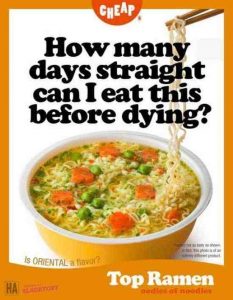

While wandering around Tokyo this past February, I felt hungry and decided it was time to eat some authentic ramen noodles. It was Saturday night and I was near Shibuya Crossing:

After leaving the lights and crowds, I began exploring dark alleys and foreboding side streets in hopes of finding, not a hole in the wall, but a culinary crevice (Tokyo is a very compact city) that only a local could discover. The night before I had visited a “hole in the wall bar” suggested by my lonely planet tour book, and to my chagrin saw groups of well-dressed white people huddled over pricey cocktails and conversing in English. Na. This time around I would wander until I found a place where the staff and patrons looked at me with either dull suspicion or obvious disgust. “Koko ni gaijin wa nan desu ka?” (What is that dirty foreigner doing here?) Yes, much better. Kon ban wa! (Good evening!)

My stomach was grumbling. I turned a corner and there it was: a ramen place that was the most inconspicuous, smallest restaurant I had ever seen. There were 4 chairs inside jammed against a crumbling wall, a flimsy counter, a narrow hallway behind the chairs, then an open kitchen without a door. I would learn later that there was only one worker present who was the host, chef, waiter, bus boy, and dishwasher. There was also only one customer; a woman sitting by herself on the middle chair.

As I set down my lucky backpack on the floor near the chair the host/chef/waiter/busboy/dishwasher gesticulated towards the entrance. The woman turned and said in perfect English, “You have to use the machine.” Next to the door was a vending machine with pictures of food on plastic squares. I learned later that many restaurants in Tokyo utilize this vending machine system: you order and pay right when you arrive, then wait for the food to be served. The pictures were blurry and did not resemble any sustenance I could recognize, so I picked the one with best mix of colors and sat down.

While reading a book on Jack Ma, I furtively inhaled the beef-spice-broth smell of the woman’s ramen bowl next to me and thought, “Yes, this is going to kick the shit out of those ramen-dime-blocks back home.”

Then I put the book down and struck up a conversation with the woman. For this essay, and the sake of anonymity, I’ll call her Matsuri. You may be wondering what this all has to do with the tragic death of a Japanese Olympian…

I asked Matsuri how she found this place. “My mother recommended it to me. She says this restaurant has the best ramen in all of Tokyo.” Even though Matsuri’s English was very good with only a slight accent, I could see via her facial expressions that her mind was in overdrive before each sentence. Nonetheless, the conversation went smoothly. I told her that I was in Tokyo for a week, by myself, and staying in 6 different AirBnB locations throughout the city. She wrote down on a napkin the name of a shrine (Meiji Jingu Shrine with a “quiet and refreshing” park)…

…and a place called Kappabashi Dougu Street (merchants have been gathering there since 1912 selling everything from hardware to restaurant supplies):

While she wrote on the napkin, I noticed slight scars on Matsuri’s wrists and hands. Before she left, I learned that she was a plastic surgeon. Immediately after revealing her occupation Matsuri assured me that it’s not like being a plastic surgeon in the United States. “It’s much easier to become a plastic surgeon here. Much less school. It’s very easy.” This was a theme throughout our conversation, her constant humility and downplay of my compliments. But I could tell she was very intelligent. She gave me her business card and I gave her mine. She left and my ramen meal arrived. Matsuri’s mother was right: it was delicious.

The next day I woke up in my $20/night AirBnB cubbyhole near the prostitute district and checked me email. Matsuri had sent me a long message:

Good morning. Here is a long list of interesting or my favorite places in Tokyo. Enjoy your trip. :D.

Below were 32 places (streets, shrines, restaurants, and museums), some with links, all with symbols next to them. At the bottom of the email was a key for the symbols: star = my favorite. * = good for people-looking. Circle = good for knowing Japanese culture. Square = funny.

Matsuri was intense, kind, and thorough…and I liked it. I emailed back asking if she wanted to have dinner that night. She said yes.

We met at Ueno park. I had just checked out the museums by there, and waited near teenage boys arm wrestling, feeling tempted to challenge one of them:

We walked to the restaurant district nearby. It was a cool, pleasant night and we threaded the bustling crowds. I almost purchased this Godzilla shirt…

…but decided I needed to start making better buying decisions, especially now that I was embarking on the path of an impoverished journalist. Matsuri led me to a busy restaurant off a side street, pushed aside some plastic curtains, and we sat down.

The dinner was relaxing and fun. We learned more about each other’s lives. Matsuri was living at home with her mother. Her parents had been divorced for 20 years and lived in separate apartments, but her grandparents still believed their children were married and living together. Despite this hidden separation, Matsuri’s parents were still pressuring her to marry. Japanese culture can be excessively polite, strict, and repressive.

Matsuri mentioned that she checked out my website. Her favorite story was, “The Aspiring Actress.” She asked me questions about the piece and I could tell that, to put it crudely, she “got it.” I was further impressed when I learned that she had never lived in an English-speaking country, although she had visited Thailand 10 times. Her speaking and reading skills were the result of school and self-study. Our first course arrived, Oden:

Oden is Japan’s “pot winter” dish and contains an assortment of boiled eggs, daikon (raddish), konjac (yam cake), and processed fishcakes stewed in a light, soy-flavored dashi broth. It’s like the “shephard’s pie” of The East.

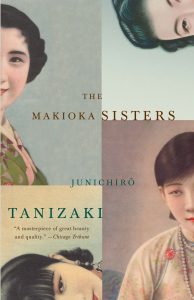

While eating our food and crushing bottles of Sake, we also discussed books. I showed her the other book I was reading:

Matsuri had read it before, and we discussed the differences in the translation. Matsuri was very disappointed in the title. In Japanese the book is called Sasameyuki, which means Light Snow. The book centers around the character named Yuki, who is one of four sisters, who drifts aimlessly and carelessly through life and is unable to find a husband, despite the pressure of her family to marry. In Japanese, there are numerous ways to describe snow, here are six different ways, and it’s meaningful that the author named his book Light Snow rather than the Makioka Sisters. We wondered about what else was lost in the English translation, and I told Matsuri about my plan to teach myself Japanese.

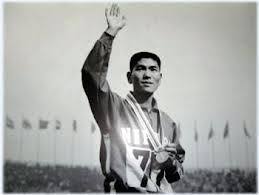

Matsuri asked if I did any sports back in American, and I told her I was a runner. She asked if I knew about the Japanese runner, Kokichi Tsuburaya. No, I did not. Kokichi was famous, in the athletics world and in Japan’s literary world. He had won the bronze medal in the marathon in the Tokyo 1964 Olympics. Then he wrote-

“Hold on, I have to go the bathroom (I was drunk).” Here’s a crappy picture I snapped on my way back from the bathroom:

The conversation moved on from Kokichi Tsuburaya and we ordered desert. I tried to pay, but Matsuri insisted that she treat me to the dinner. Then we left the restaurant…

On my last day in Tokyo I emailed Matsuri asking if she wanted to hang out again. I was drinking beer with Wolfgang (a physicist who I met my first day who was studying at Keio University) and we decided to get some late-night snacks. Tokyo is not a late-night town. The subways close at midnight and most of the restaurants close too. We began wandering around Shimbashi and I snapped this picture of a drunkenly “salary man” passed out against a pole:

Finally, we found a place that was open and selling Takoyaki, or fried balls. Tako means octopus and yaki (which sounds similar to ‘yucky’) means fried. Here they are:

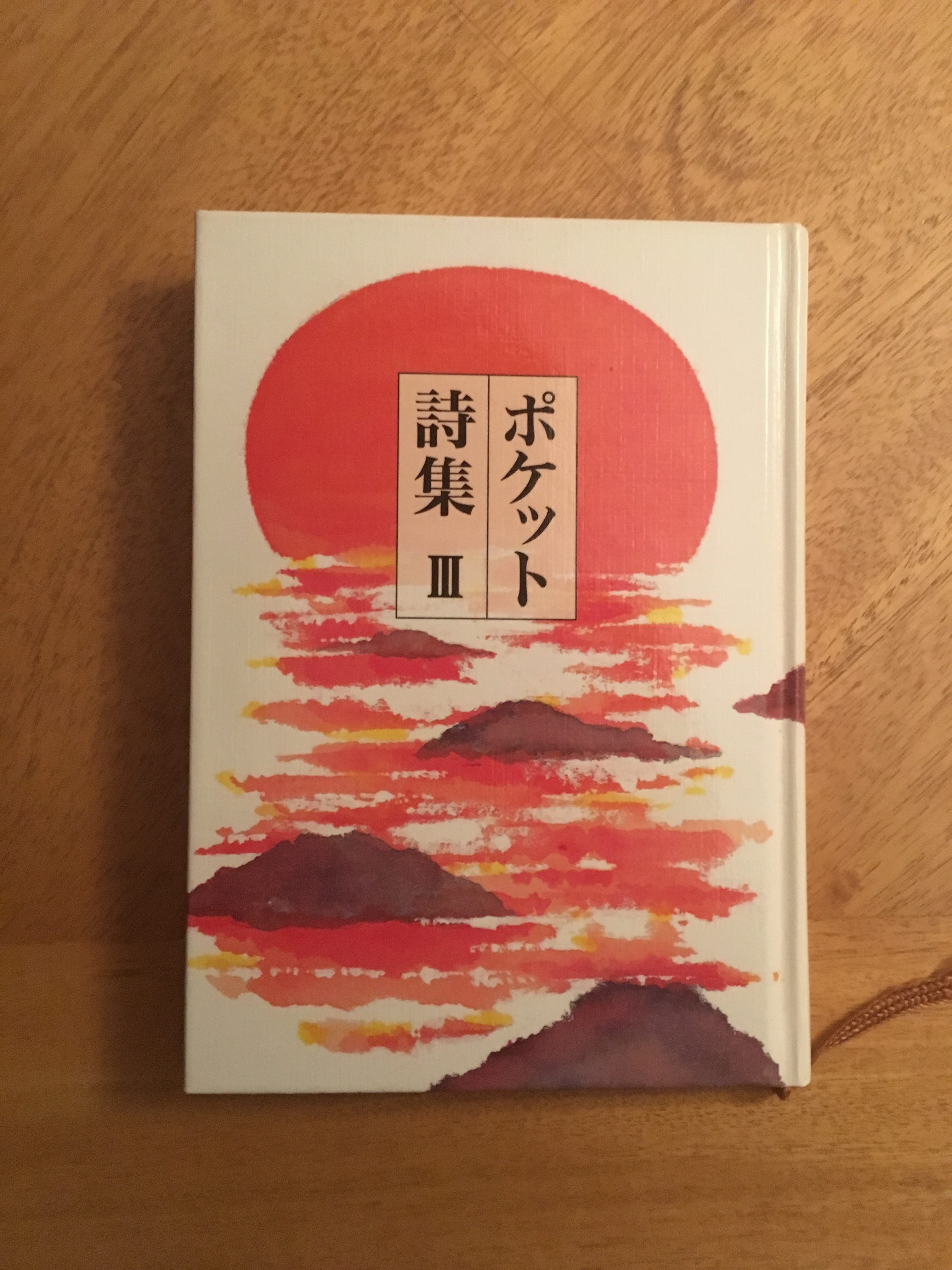

Matsuri met us there after work and we drank, eat Takoyaki, and talked. We stood at a table near the street and the chilly breeze complemented the hot balls I kept impatiently scorching the roof of my mouth with. We had a good time. I told them how much I had enjoyed my trip and swore that I WOULD RETURN SPEAKING JAPANESE. Matsuri gave me a book of poems:

I can’t read them yet, but someday I will.

As I hugged Matsuri goodbye, I thought she looked preoccupied and sad. I even thought there were tears in her eyes, but that could have been the street-lamp reflections and the wind. She said, “I forgot to tell you the story of Kokichi Tsuburya!”

“It’s alright, I’ll look him up later.”

“Goodbye. It was nice meeting you!”

“It was nice meeting you too. Goodbye Matsuri!” She left.

On the plane back to New York City, I looked up Kokichi Tsuburya. Over the next couple months I sporadically researched his life. Here is his tragic story:

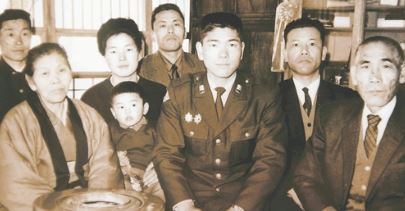

Kokichi was born in Sukagawa, Fukushima in 1940. He was 1/7 children:

The family planted rice and raised livestock. When each child reached the age of 10 they were put to work. The father, Koshichi Tsuburya, was extremely strict and believed his children required extra discipline to ensure they did their chores. Like a drill Sargent, he ordered them around yelling, “Go Forward!” “Right Face!” and, “Attention!” On top of cooking, cleaning, and planting, he trained them to use bayonets and hit them whenever they were not obedient.

As a young boy Kokichi loved to run, especially with the family dog. At the age of 5, though, he felt acute pain in his legs and back. Koshichi noticed that his son’s left leg was shorter than his right. When they brought him to hospital to confirm the diagnosis, they also learned that Kokich had tuberculosis arthritis, which causes pain in the weigh-bearing joints of the ankles, knees, and hips. Kokichi felt pain whenever he ran.

Despite this pain, Kokichi kept on running. He looked up to his older brother, Kikuzo, who ran in competitions. They ran together and even though Koichi was 7 years younger, he kept up. The brothers would go on runs late at night. Their father did not approve. “You can’t earn a living off of running,” he said. So the sons would sneak out to run when their father was taking his evening bath.

Koshichi finally confronted his son and asked, “If you run, will you take this all the way?” Kokichi replied, “Yes,” and the father added, “If you decide to do this, do not stop halfway.”

Kokichi dedicated himself completely and in high school he qualified for the National 5000 meter race. He did not win. Without anyone urging him to do so, he shaved his head to publicly account for his defeat.

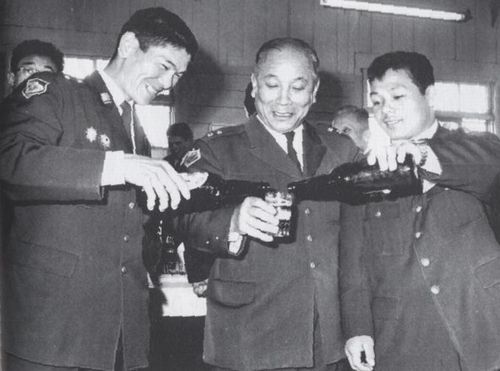

After graduating from high school Kokichi joined the Ground Self-Defense Force, following in the footsteps of his father and becoming a soldier. He became a 1st lieutenant.

At the age of 24 he qualified for the Tokyo Olympics in the 10,000 meters and the marathon. He also fell in love with a girl named Eiko, who he planned to marry after the games.

The Tokyo Olympics was historic in various ways: it was the first Olympics held in Asia, it was the first time South Africa was barred from taking part due to its apartheid system, and they were the first games to be telecast internationally without the need for tapes to be flown overseas. They were the first Olympic games to have color telecasts and of the 5,151 participants 4,473 were men and 678 were women. In the 2020 Tokyo Olympics there will be nearly an equal ratio of men/women competitors and there will be mixed events (men and women competing in the same relay, such as the 4×400 meters). We’ve come a long way.

The competitions were held in October to avoid the city’s midsummer heat and humidity. On the 14th of October, Kokichi raced the 10,000 meters and placed 6th. This would be the last time the Olympics used a traditional cinder track for the track events, as a smooth synthetic all-weather track would be used for the first time at the 1968 games.

The last event of the games was the marathon. Kokichi was entered in the competition with his friend and teammate Kenji Kimihara. No doubt they discussed that Japan had not won a single track medal during the entire Olympic games, and this marathon would be the last chance for them to win one for their country.

Abede Bikila won the gold, becoming the first and only man to win the gold in the marathon in two, consecutive Olympics (he won gold in 1960 running barefoot). Here’s good amateur video of his finish, where immediately upon crossing the finish line he began doing calisthenics. Great athletes never stop.

Here’s a video with great footage:

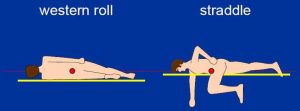

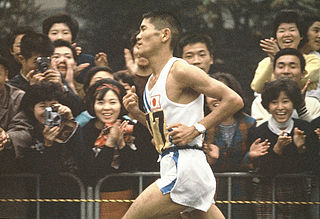

When Kokichi entered the Olympic stadium he was in second place and greeted by a roar from the crowd. But right behind him was Basil Heatley, who would pass him in the last 200 meters (13:59). Kokichi was devastated that he would let a competitor pass him in front of so many Japanese people, and there was a collective groan when he lost. Later, Kokichi would tell his friend Kenji Kimihara (who was 23 years old during the race and placed 8th):

“I committed an inexcusable blunder in front of the Japanese people. I have to beg their pardon by running and hoisting the Hinomaru [national flag] in Mexico [the next Olympics.]

After the games, Kokichi began training hard. He was a national hero and vowed to do better in 1968. He also wanted to marry Eiko. Kokichi’s coach at the Self-Defense Forces Athletics school, Hiro Hatano, supported the marriage, and so did Kokichi’s parents.

But Hiro Hatano’s boss did not approve of the marriage. In 1966, coach Hatano’s boss declared that Kokichi needed to focus 100% on his training and that a marriage would distract him from his goals. In Japan, there are rigid hierarchies, and this system is even more strict in the military.

Hatano’s boss brought Hatano, Eiko, and Eiko’s mother together to discuss how the marriage would have to wait until after the Olympic Games. That way Kokichi could focus solely on his training. Kokichi was not at the meeting.

Hatano protest this decision, but was left with the task of telling Kokichi that he couldn’t marry Eiko. Hatano refused and ended up being demoted and removed from his coaching position.

Eiko was devoted to Kokichi and still wanted to marry him, but Eiko’s mother was not supportive any longer. Eiko’s mother was anxious that a marriage to a famous, bronze-medalist with the whole country counting on him would add a burden to his wife. She also wasn’t confident that a marriage in 2 years was certain. And since Eiko was 22 years old, she could lose her chance to marry well.

The marriage was broken off. Since Kokichi didn’t have a coach anymore, he began training on his own. He became plagued with injuries. He felt intense pain in a slipped disk that he had hurt years ago. In 1967, an injury to his Achilles tendon required surgery.

At the end of 1967 Kokichi returned home for a New Year’s holiday break. His father was distraught with news that he did not want to tell his son. But he thought it was best to tell his son the news before he found out on his own. He told him that Eiko had married someone else. Kokichi’s response was, “Oh, Eiko-san is married. That’s good for her.”

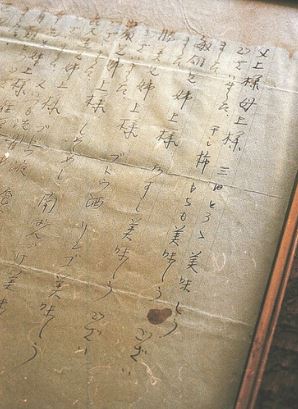

Soon after Kokichi returned to his Self-Defense Force base to train. But he couldn’t run a step because he suffered from lumbago. On Janurary 8th, 1968, teammates of Koichi entered his dorm room to find that he had slit his wrists and killed himself. He left behind a suicide note:

The suicide note is consider by the Japanese literary world as a masterpiece for its simplicity and banality. Yukio Mishima (who ended up killing himself 12 years later during a military coup through seppuku) described it as beautiful, honest and sad. Kensaburo Oe, the Nobel Prize winner in 1994, believed it was a cultural marker of the 1960s Japanese ethos. Here it is:

My dear Father, my dear Mother: I thank you for the three-day pickled yam. It was delicious. Thank you for the dried persimmons. And the rice cakes. They were delicious, too.

My dear Brother Toshio, and my dear Sister: I thank you for the sushi. It was delicious.

My dear Brother Katsumi, and my dear Sister: The wine and apples were delicious. I thank you.

My dear Brother Iwao, and my dear Sister: I thank you. The basil-flavored rice, and the Nanban pickles were delicious.

My dear Brother Kikuzo, and my dear Sister: The grape juice and Yomeishu were delicious. I thank you. And thank you, my dear Sister, for the laundry you always did for me.

My dear Brother Kozo and my dear Sister: I thank you for the rides you gave me in your car, to and fro. The mongo-cuttlefish was delicious. I thank you.

My dear Brother Masao, and my dear sister: I am very sorry for all the worries I caused you.

Yukio-kun, Hideo-kun, Mikio-kun, Toshiko-chan, Hideko-chan, Ryosuke-kun, Takahisa-kun, Miyoko-chan, Yukie-chan, Mitsue-chan, Akira-kun, Yoshiyukikun, Keiko-chan, Koei-kun, Yu-chan, Kii-chan, Shoji-kun: May you grow up to be fine people.

My dear Father and my dear Mother, Kokichi is too tired to run anymore. I beg you to forgive me. Your hearts must never have rested worrying and caring for me.

My dear Father and Mother, Kokichi would have liked to live by your side.

*

When Kokichi Tsuburaya was found dead in his dorm room he was holding on to his bronze medal.

Epilogue:

For months I’ve planned to end this essay with Kokichi dead in his dorm room and holding on to his bronze medal…next to a suicide note about delicious food. But due to various life circumstances and additional research, there’s another part of the story I want to tell:

Kenji Kimihara:

Kenji was Kokichi’s teammate and friend at the 1964 Olympics, whom Kokichi confessed, “I made an inexcusable blunder…” Two years after the 1964 Olympics Kenji won the Boston Marathon. Then, in the 1968 Olympics, 9 months after Kokichi’s suicide, Kenji would win the silver medal in the marathon by 14 seconds. No doubt he felt redemption for Kokichi, winning the medal that Kokichi missed by 3.6 seconds.

In 2016 Kenji Kimihara ran the Boston marthon, 50 years after his victory. He was 75 years old and ran the marathon in 4 hours 53 minutes and 14 seconds. There was little press given to this accomplishment.

We are all surrounded by sadness and lost opportunities. But we’re all, also, headed to the same, dark place. What’s tragic to me about Kokichi’s death was not his suicide or what caused him to take his life, but what he missed. Kenji, while he’s an old man, is still living, breathing, learning, and running. He is a reminder to me that life, with all its pain, confusion, glory, and hope, will always move on, past all tragedy and defeat. He is a reminder that life is only out there, waiting, for the living.

Subscribe below: