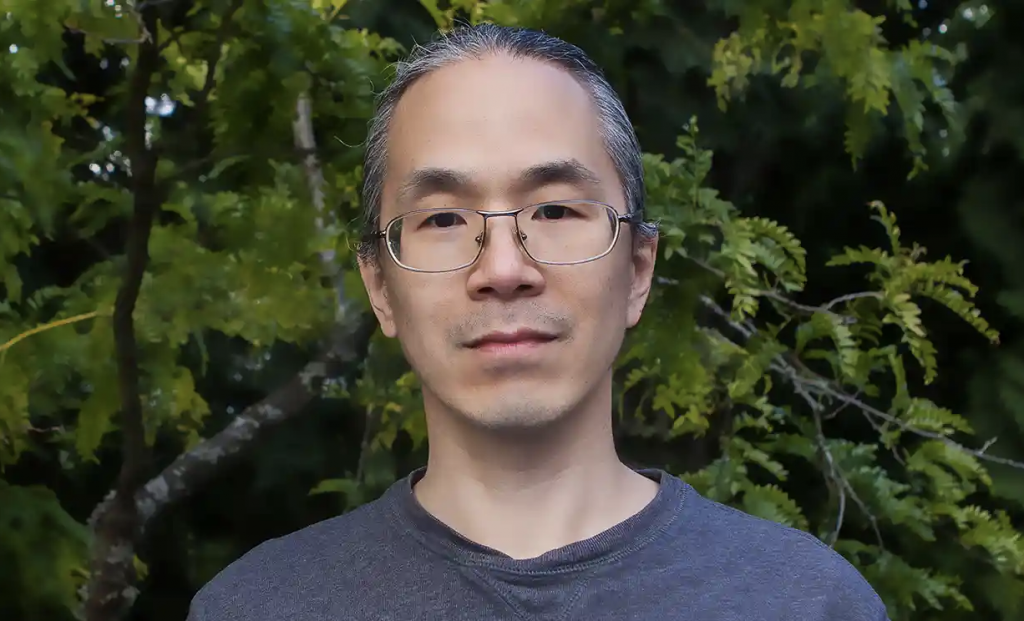

I met that elderly author, Haruki Murakami, in a small, Japanese-style town outside of Kyoto, some three years ago. He was boring or, more precisely, very boring, but I happened to spend a night in his company.

I was travelling around in Japan, wherever the spirits or my Lonely Planet guide book led me, when I received an email from Murakami to meet for a beer. I knew from his books that Murakami likes beer. But why would he send an email to a nobody like me to meet for a drink? I had no idea.

It was already past 8 p.m. when I arrived at the town and got off the train. Autumn was nearly over, the sun had long since set, and the place was enveloped in that dark-blue darkness particular to places where the sun has set. A cold, biting wind blew from somewhere, sending formless pieces of trash rustling along the street.

I walked through the center of town in search of a place to stay, before meeting the famous author, but none of the decent inns would take in guests after the dinner hour had passed. I stopped at five or six places, but they all turned me down flat. Finally, in a deserted area outside town, I came across an inn that would take me. It was a desolate-looking, ramshackle place, almost a flophouse. It had seen a lot of years go by, but it had none of the quaint appeal you might expect in an old inn. Fittings here and there were ever so slightly slanted, as if slapdash repairs had been made that didn’t mesh with the rest of the place. I doubted it would make it through the next earthquake, and I could only hope that no temblor would hit while I was there.

The inn didn’t serve dinner, but breakfast was included, and the rate for one night was incredibly cheap. Inside the entrance was a plain reception desk, behind which sat a completely hairless old man – devoid of even eyebrows – who took my payment for one night in advance. The lack of eyebrows made the old man’s largish eyes seem to glisten bizarrely, glaringly. On a cushion on the floor beside him, a big brown cat, equally ancient, was sacked out, sound asleep. Haruki would like that cat, I thought. He would probably write ten, boring pages about it. The cat was snoring loud. There was probably something wrong with it. Everything in this inn seemed to be falling apart.

The room I was shown to was cramped, like the storage area where one keeps futon bedding; the ceiling light was dim, and the flooring under the tatami creaked ominously with each step. But it was too late to be particular. I told myself I should be happy to have a roof over my head, a futon to sleep on, and a famous author contacting me for god knows what.

I put my one piece of luggage, a suitcase, down on the floor and set off back to town. (This wasn’t exactly the type of room I wanted to lounge around in, especially when I had an approaching rendezvous.) I went into a nearby soba-noodle shop and had a simple dinner. I didn’t want to have an empty stomach before drinking with Haruki, because I think he drinks like a fish. It was that soup or nothing, since there were no other restaurants open. I had a beer with the dinner, some bar snacks, and some hot soba. The soba was mediocre, the soup lukewarm, but again, I wasn’t about to complain. It beat going to bed later on just beer and vomiting in the morning, because who knows if Haruki would give me food. After I left the soba shop, I thought I’d buy some snacks and a small bottle of whisky to give to Haruki (he likes whiskey), but I couldn’t find a convenience store. It was after nine, and the only places open were the shooting-gallery game centers typically found in the town (according to my guide book). So I hoofed it to the address Murakami had sent me. Our rendezvous was for 9:37pm.

Compared with the shabby neighborhood where I was staying, the area where Murakami wanted to meet was surprisingly wonderful. The homes, which looked like Buddhist temples, were spaced far apart, the streets were clean, and the atmosphere was quiet and peaceful.

I was approaching a house when a man seemed to appear out of nowhere at my side. Was he hiding in the bushes? “Excuse me,” he said in a low voice. I was about to shout and run away, when I realized it was Haruki. He gazed intently at my face, his eyes narrowed, for all the world like an anthropologist studying an indigenous native of a long-lost tribe.

“How is the thing?” he asked me.

“Um, what thing?”

“The thing.” I was embarrassed, so I replied,

“It’s very nice. Thank you.” My voice reverberated densely, softly, in the night air. It sounded almost mythological, not like my own voice but, rather, like an echo from the past returning from deep in the forest. And that echo was…hold on a second. What was Murakami doing here on the street? Why wouldn’t he wait for me inside his home?

“Shall I help you become a better writer?” he asked, his voice still low. He had the clear, alluring voice of a baritone in a doo-wop group. But nothing was odd about his voice: if you closed your eyes and listened, you’d think it was an ordinary person speaking.

“Yes, thanks,” I replied. It wasn’t as if I’d been waiting all my life hoping that Murakami would give me writing advice, but if I turned him down I was afraid he might not invite me inside for a beer. I figured it was a kind offer on his part, and I certainly didn’t want to hurt his feelings. So I nodded and added, “Please, help me write, as…as good as you,” and followed him into his yard then his house.

There was no furniture inside the house except a refrigerator in the center of a big room. Haruki opened it and gave me a beer.

“It’s got very cold these days, hasn’t it?”

“That it has.”

“Before long this place will be covered in snow. And then they’ll have to shovel snow from the roofs, which is no easy task, believe me.”

There was a brief pause, and I jumped in. “So how do you write so many books that are so interesting?”

“I just do it,” Haruki replied briskly. He probably often received questions like this and was annoyed with them. “I started writing at the age of twenty-nine, because I felt like it, and before I knew it I was selling millions of books and winning awards. I lived for quite a long time without writing, around Tokyo, working in a coffee house and a jazz bar.

“What part of Tokyo?”

“Kokubunji.”

“That’s a nice area.”

“Yes, it is a pleasant residential area with excellent transportation links. There are many parks and it is a popular location for young families.”

Our conversation paused at this point. Haruki continued drinking his beer (I did too) and all the while I tried to puzzle things out rationally. Why was I here? Why did he invite me? Did he want something? How did he even think to contact me? This was Haruki Murakami, for goodness’ sake.

“I grew up in America,” I said, a basically meaningless statement.

“I know. Americans buy millions of my books. I like that,” he said in a friendly tone.

“What else did you think of Kokubunji when you lived there?”

“Well, even though it is a nice place to raise a family, my wife and I decided not to have children.” This wasn’t really the answer to my question.

“You wanted to dedicate everything to literature?” He frowned.

“No. We made this decision before I started writing.”

“Oh.”

“I like music though. Especially classical music you’ve never heard of. I’m very cultured and refined.” I decided to continue with this topic of conversation, because I knew from Murakami’s books that he was always name-dropping classical songs and writing boring pages about his opinions on composers.

“Like who?”

“Bruckner and Richard Strauss.”

“You enjoy Bruckner. I often listen to Bruckner!” (I’d never heard of him.)

“Yes. His Seventh Symphony. I always find the third movement particularly uplifting.”

“I…um…often listen to his Ninth Symphony,” I chimed in. (I hoped Brucker wrote at least that many.)

“Yes, that’s truly lovely music,” (Phew.)

“So why didn’t you have any children?”

“I am a very patient person, a person who values order and regularity above all, so no kids for me. Kids are chaos. I am a serious person whose favorite saying is that the repetition of accurate facts is the true road to wisdom. My wife is a quiet, sweet person, always kind to me. We get along well, and I hesitate to mention this to a stranger like you, but, believe me, my nighttime activities can be quite intense.”

“Really,” I said.

Haruki started to walk out of the room. “Thanks for your patience and for visiting me,” he said, and bowed his head. I thought his polite gratitude very Japanese.

“Thank you,” I said. “What you said just now was…good. So, do you live in this house?”

“I do. Sometimes. I sleep on the floor in the other room. The neighbors are kind and leave me alone. I can’t live in cities anymore. Too much attention. Here, the people don’t care if I’m a famous writer or not. They let me work and drink my beer without taking photographs.” I knew Haruki was known for being a recluse (in Japan), among other things.

“Have you been working and drinking here for a long time?” I asked.

“It’s been about thirteen years, off and on.”

“But you must have gone through all sorts of things before you arrived here.”

Haruki gave a quick nod. “Very true.”

I hesitated, but then came out and asked him, “If you don’t mind, could you tell me why I’m here? Why you invited me?”

Haruki considered this, and then said, “Yes, you are right to ask me that. It might not be as interesting as you expect, but I’d prefer to tell you later tonight, at a different location. Would that be convenient?”

“Certainly,” I replied. “I’d be grateful if we also drank beer then.” (It would make his boring conversation more enjoyable.)

“Understood. Some cold beers it is. Would Sapporo be all right?” I knew there was Sapporo at my inn.

“That would be fine. So you like beer?”

“A little bit, yes.”

“Then please bring two large bottles.”

“Of course. If I understand correctly, you are staying in the Araiso Suite, on the second floor? Let’s drink there.” This scared me a bit.

“Ah, that’s right.”

“It’s a little strange, though, don’t you think?” Haruki said. I thought he was going to explain how he knew where I was staying, but I was wrong. “An inn in the mountains with a room named araiso – ‘rugged shore.’” He chuckled. I’d never in my life thought I’d hear Haruki Murakami chuckle. But I guess famous authors do laugh, and even cry, at times. It shouldn’t have surprised me, given that famous authors are human too.

“By the way, should I call you Haruki, or Mr. Murakami?”

“Just call me friend.”

Haruki finished his beer, put the bottle in the fridge, turned, and gave a polite bow, then walked deeper into the house and disappeared.

It was a little past eleven when Haruki came to the Araiso Suite, bearing a tray with two large bottles of beer. I assumed he had got them from downstairs. In addition to the beer, the tray held a bottle opener, two glasses, and some snacks: dried seasoned squid and a bag of kakipi– rice crackers with peanuts. Typical bar snacks. This was one author who knew how to throw a party!

Haruki was dressed in a peculiar way: gray sweatpants and a thick, long-sleeved shirt with “I <3 NY” printed on it, probably some kid’s hand-me-downs. Weird.

There was no table in the room, so we sat, side by side, on some thin zabuton cushions, and leaned back against the wall. Haruki used the opener to pop the cap off one of the beers and poured our two glasses. Silently we clinked our glasses together in a little toast.

“Thanks for the drinks,” Haruki said, and happily gulped the cold beer. I thought this was odd to say, since he brought the beer, but I went with it. Maybe he had charged them to my room? I drank some as well. Honestly, it felt strange to be seated next to Haruki Murakami, sharing a beer, but I guess you get used to it.

“A beer after work can’t be beat,” said Haruki, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. “But, for a famous author, the opportunities to have a beer with a nobody-writer like you are few and far between, believe it or not.”

“How often do you contact nobody-writers like me?”

“Once every couple of years.”

“Oh.”

Haruki had finished his first glass, so I poured him another.

“Much obliged,” he said politely.

“Where is your wife right now?” I asked.

“She’s with…a friend,” Haruki answered, his face clouding over slightly. The wrinkles beside his eyes formed deep folds. “Whenever she wants to meet with a friend, go on trips or vacations with him, I contact nobody-writers who I discover on the internet. I don’t have friends. For years I thought I could live peaceably without friends, but that didn’t work. People were kind to me, but I just couldn’t connect with them, I just couldn’t express my feelings well to them. We had little in common, and communication wasn’t easy. ‘You talk funny,’ they told me, ‘You’re so boring,’ and they sort of mocked and bullied me. Women would giggle when they looked at me. I am extremely sensitive, as you probably know from my best-selling books. Women found the way I acted comical, and it annoyed them, irritated them sometimes. It got harder for me to be around people, so eventually I went off on my own. But I needed connection, so I started contacting random bloggers to meet me for a drink.”

“It must have been lonely for you, before contacting nobody-writers.”

“Indeed it was. I had to emotionally-survive on my own when my wife was busy or traveling. But the worse thing was not having anyone to communicate with. I couldn’t talk with people. Isolation like that is heartrending. The world is full of humans, but I couldn’t start up a conversation with whomever I happened to come across. Do that and there’d be hell to pay. The upshot was that I wound up sort of neither here nor there, not part of the common herd, nor part of the literary elite. It was a harrowing existence.” (Boring, I thought, Time to change the subject.)

“And you didn’t know about Bruckner, then.”

“True. That’s part of my life now,” Haruki said, and drank some more beer. I studied his face. It was red, so I assumed he was drunk. I had figured Haruki could hold his liquor, but I guess I was wrong. Or maybe Haruki’s face turned red whenever he was drinking, no matter what the quantity.

“The other thing that tormented me, before I married, was my relations with females.”

“I see,” I said. “And by ‘relations’ with females you mean – ?”

“In short, I didn’t feel a speck of sexual desire for women. I had a lot of opportunities to be physical with them, but never really felt like it. I guess I regret not doing anything.”

“So women didn’t turn you on, even though you liked them?”

“Yes. That’s exactly right. It’s embarrassing, but, honestly, I could only be sexually attracted to a woman I loved. And I’ve only ever loved my wife.”

I was silent and drained my glass of beer. I opened the bag of crunchy snacks and grabbed a handful. “That could lead to some real complications, I would think.”

“Yes, real complications, indeed. Me being a sensitive and shy, there was no way I could expect women to understand my complicated desire. Plus, it runs counter to culture, where young men are supposed to have relations with many women, ‘sow their wild oats,’ they say.”

I waited for the beer to make his conversation less boring. Haruki rubbed hard behind his ear and continued.

“And now…” He squinted his eyes. “So I found another method of dealing with my complex desire.”

“What do you mean by ‘another method.’”

Haruki frowned deeply. His red face turned a bit darker.

“You may not believe me,” Haruki said. “You probably won’t believe me, I should say. But, from a certain point, after I was married, I started using the experiences I had with women from my past, combined with the feelings I have for my wife, to create literature.”

“How?”

“I seem to have been born with a special talent for it. I can write from memory, add in dream-live, abstract elements, and people like it.”

A wave of confusion hit me. Haruki wasn’t making any sense.

“I’m not sure I get it,” I said. “When you say you mix your memories with dream-like elements, does that mean your stories aren’t supposed to have any meaning?”

“No. They don’t lose their meaning. I write about my past, a fragment. But when I mix in a dream-like element it becomes less substantial, lighter than before. So I can go deeper in the memory despite the pain. Like when the sun clouds over and your shadow on the ground gets that much paler. And, depending on the memory, I become less aware of the loss. The pain transforms into a sense that something’s a little off, but also bearable.”

“But do the women you write about know what you’re doing? That you are using their past for your literature?”

“Yes, of course, some of them do. But most of the time the women have forgotten me. Quite a shock to the ego, as you might imagine. And when they read my stories, if they even do, they may not even recognize the character as themselves. In some cases, they suffer through something close to an identity crisis, one of them told me. And it’s all my fault, since I took the experience I had with them and turned it into literature. I feel very sorry about that. I often feel the weight of a guilty conscious bearing down on me. I know it’s wrong, yet I can’t stop myself. I’m not trying to excuse my actions, but my dopamine levels force me to do it. Like there’s a voice telling me, “Hey, go ahead, write that senseless dream sequence mixed with your past with a woman. It’s not illegal or anything, and millions of people will buy your books anyway.”

I folded my arms and studied the famous author. Dopamine? Finally, I spoke up. “And the women you write about, they are the ones you had intimate experiences with but never loved. Do I have that right?”

“Exactly.”

“How many women?”

With a serious expression, Haruki totaled it up on his fingers. As he counted, he was muttering something. He looked up. “Seven in all. I have been intimately involved with seven women before my wife.”

Was this a lot, or not so many? Who could say?

“So how do you do it?” I asked, “Combine your past experiences with dream-like elements?”

“It’s mostly by will power. Power of concentration, psychic energy. But that’s not enough. I need to meet with a nobody-writer to talk about what I do, before I can actually do it. Communication is the path to understanding. Because we, you and I, have no connection to each other, I can talk freely. I’m pretty skilled at talking freely about my writing.”

“So when you need inspiration you contact a nobody-writer on the internet?

“Precisely. I stumbled upon your blog by chance, and since I’m working on a story now and my wife is with her…friend, I sent you an email. Now I can go back to writing.”

“So that’s it? You’re using me for literature?”

Haruki nodded sharply. “I know it sounds lowly, but I never do anything unseemly. You won’t be in my books explicitly. I agree it’s a bit strange, but it’s also a completely pure, platonic act. I simply have a beer with a stranger, secretly, talk and talk, and it helps me write. For me, this experience is like a gentle breeze wafting over a meadow.”

“Hmm,” I said, dreadfully bored. “I guess you could even call your complex desire, your past inability to feel sexual attraction without loving a woman, the ultimate form of romantic love.”

“Agreed. But it’s also the ultimate form of loneliness (Here we go again, I thought. Murakami and his goddamn loneliness). Like two sides of a coin. The two extremes are stuck together and can never be separated.”

Our conversation came to a halt here, and Haruki and I silently drank our beer, snacking on the kakipi and the dried squid.

“Have you written about a woman from your past recently?” I asked.

Haruki shook his head. He grabbed some hair on his head, as if making sure that he still had hair. “No, I haven’t written about a woman from my past recently. Soon, though. That’s why I contacted you. Thanks to this encounter, I have found a measure of clarity and peace. I will be able to write about the woman now, one of the seven women in my heart.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” I lied.

“I know this is quite forward of me, but I was wondering if you’d be kind enough to allow me to give my opinion on the subject of love.” Oh god no. Could he get any more boring? I saw that there was still some beer. I nodded my head and began chugging.

“I believe that love is indispensable fuel for us to go on living. Someday that love may end. Or it may never amount to anything. But even if love fades away, even if it’s unrequited, you can still hold on to the memory of having loved someone, of having fallen in love with someone. And that’s a valuable source of warmth. Without that heat source, a person’ heart – including my heart – would turn into a bitterly cold, barren wasteland. A place where not a ray of sunlight falls, where the wildflowers of peace, the trees of hope, have no chance to grow.” He seemed to be reciting something he had recently written, or was about to write. “Here in my heart, I treasure the names of those seven women I tried to love, but failed, or can’t love anymore.” Haruki laid a palm on his chest. “I plan to use these memories, along with random encounters such as this one, as my own little fuel source to burn on cold nights, to keep me warm as I live on what’s left of my own little life.”

Haruki chuckled again, and lightly shook his head a few times.

“That’s a strange way of putting it, isn’t it?” he said, “Little life. Given that I’m a famous author, with supposedly a big life. Hee hee!”

It was past midnight when we finally finished drinking the two large bottles of beer. “I should be going,” Haruki said. “I got to feeling so good I ran off at the mouth, I’m afraid. My apologies.”

“No, I didn’t mind,” I lied. At least he was conscious of how much he been blabbering on. But I mean, sharing beer and chatting with a famous author was a pretty unusual experience in and of itself. I should be more thankful. Add to that the fact that this famous author contacted me randomly online, loved name-dropping classical composers, and writes about the same, seven women from his past because he had intimate experiences with them (but didn’t love them).

As we said goodbye, I handed Haruki a small bottle of whiskey that I had stolen from the closed-down bar when I arrived back at the inn. “It’s not much,” I said, “but please enjoy this whiskey.”

At first Haruki refused, but I insisted and he finally accepted it. He put the bottle in the pocket of his sweatpants.

“It’s very kind of you,” he said. “You’ve listened to my absurd life story and writing process, treated me to beer, and now this generous gesture.” (But it was him who brought the beer, maybe he was drunk, or maybe he did charge my room.) “I can’t tell you how much I appreciate it.”

Haruki put the empty beer bottles and glasses on the tray and carried it out of the room.

The next morning, I checked out of the inn and went to Tokyo. At the front desk, the creepy old man with no hair or eyebrows was nowhere to be seen, nor was the aged cat who snored loudly. Instead, there was a fat, surly middle-aged woman, and when I said I’d like to pay the additional charges for last night’s bottles of beer (I assumed Haruki had charged them to my room, since he kept thanking me for the beer), she said, emphatically, that there were no incidental charges on my bill. “All we have here is canned beer from the vending machine,” she insisted. “We never provide bottled beer.”

Once again I was confused. I felt as though bits of reality and unreality were randomly changing places. Nonetheless, how kind of Murakami to buy me beer!

I was going to bring up Haruki Murakami with the middle-aged woman, but decided against it. Maybe Haruki didn’t actually visit me, maybe the man was an imposter, and it had all been an illusion, the product of a lonely, Japanese man who looked just like Murakami preying on nobody-writers like me. Or maybe what I saw was a strange, realistic dream (thinking about Murakami so much has really made my thoughts more dream-like). If I came out with something like, “Last night the famous author Haruki Murakami visited me in my room,” things might go sideways, and, worst-case scenario, she’d think I was insane. Chances were that Murakami was a town secret, and the inn couldn’t acknowledge him publicly for fear of him moving away or getting angry.

On the train ride to Tokyo, I mentally replayed everything Haruki Murakami told me. I jotted down the details, as best I could remember, in a notebook that I used for work, thinking that when I got back to Tokyo I’d write the whole thing as a blog post from start to finish.

If Haruki Murakami actually met me– and that was the only way I could see it – I wasn’t at all sure how much I should accept of what he had told me over beer. It was hard to judge his story fairly. Was it really possible that he used his experiences from women in the past to write literature? Were the dream-like elements in his stories just cheap, easy ways to cope with his memories and pain? Maybe Haruki was a pathological liar. Who could say? Naturally, there are numerous famous authors with mythomania, but, if Murakami harnessed his sickness to sell millions of books, who cares if he is a habitual liar who bizarrely contacts nobody-writers for a beer and to hear himself talk?

I’d encountered thousands of people working as a bartender in New York City during my twenties, and had become pretty good at sniffing out who could be believed and who couldn’t. A bullshit detector, you can call it. When someone talks for a while, you can pick up certain subtle hinds and signals and get an intuitive sense of whether or not the person is believable. And I just didn’t get the feeling that what Haruki was telling me was made-up bullshit. Then again, he also worked in a restaurant for years, so maybe he had developed a way to skillfully bullshit gullible people, undetected. But the look in his eyes and his expression, the way he pondered things every once in a while, his pauses, gestures, the way he’d get stuck for words – despite being boring, nothing about it seemed artificial or forced. And, above all, there was the total, even painful honesty of his confession.

My relaxed solo journey over, I returned to the whirlwind routine of ex-pat life in a city. Even when I don’t have any major work-related assignments, somehow, as I get older, I find myself busier than ever. And time seems to steadily speed up. In the end I never told anyone about meeting Haruki Murakami, or wrote anything about him. Why try if no one would believe me? Unless I could provide proof – proof, that is, that Haruki contacted other nobody-writers for beer – people would just say that I was “making stuff up again.” And if I wrote about him as fiction the story would lack a clear focus or point, and look like I was just complaining about his writing being so boring, and not understanding why so many readers praise and read his books, when I find them achingly dull. I could well imagine a reader of my blog looking puzzled while reading my post, saying to themselves, “I hesitate to ask, since you’re the author of this post, but what is the theme of this story supposed to be?”

Theme? Can’t say there is one. It’s just a confession about an old, famous writer who pumps out boring books and asks nobody-writers to meet him for beer in a tiny town outside Kyoto, who feels nostalgia for the women he had intimate experiences with but never loved. Where’s the theme in that? Or the moral?

And, as time passed, the memory of my Murakami encounter began to fade. No matter how vivid memories may be, they can’t conquer time.

But now, three years later, I’ve decided to write about it, based on notes I scribbled down back then. All because something happened recently that got me thinking. If that incident hadn’t taken place, I might well not be writing this.

I had a journalism networking event in the coffee lounge of hotel in Akasaka. Near the end of the event I was talking to an old woman, the editor of a travel magazine. Despite being old, she was attractive: long hair, a lovely complexion, and large, fetching eyes. She was one of those passionate, energetic, ageless humans, who still have sexual appeal even when they’re elderly. She was an able editor. And still single. I think she wanted to sleep with me. We’d worked together quite a few times, and got along well. We sat in a corner and chatted over coffee for a while.

Her cell phone rang and she looked at me apologetically. I motioned to her to take the call. She checked the incoming number and answered it. It seemed to be someone important. She talked for a while in Japanese, checking her pocket planner, and then shot me a mischievous look.

“It’s Haruki Murakami,” she said to me in an excited voice, her hand covering the phone. “We used to date a lifetime ago.”

I gasped, but, as casually as I could, I took a sip of coffee. She nodded and relayed information to the famous author on the other end of the line. Then she hung up and giggled.

“We dated when we were teenagers.”

“Does he call you often?” I asked.

She seemed to hesitate, but finally nodded. “Yes, it’s happening a lot these days. I don’t know why.”

“Does he miss you?”

She shook her head decisively. “No, not at all. We’ve always been on platonic terms since we broke up. He loves his wife. He’s faithful. But sometimes we meet up in secret. I’ve never been able to figure him out. When we were together, he was so distant. After, when we became sort-of friends, there was this animal hunger about him. As if he desperately wanted to get closer, but just couldn’t. Maybe I’m crazy.”

“No, I don’t think you are.”

She squinted and thought more about it. “About half a year ago, I think, I remember I went to visit a cherry blossom orchard, near where I grew up. It was the place where Haruki and I first kissed. When I arrived he was there, wandering around the trees, with tears on his cheeks. He didn’t see me. I was so scared when I saw him, I ran away.”

“This might be an odd thing to ask, but, when you’ve read his books, did you ever notice that some of the characters were based off of you?”

She pursed her lips, then smiled. “I’ve never read his books. I’ve tried, but I just can’t. They are all so boring. Banal. He writes for the masses, particularly the western masses. We have a word for what he writes, in Japanese: batakusai, which means “stinking of butter.” His writing is a mish-mash of katakana and hiragana, using borrowed western terms, and his stories have no point.”

She took a sip of coffee. I waited for her to go on.

“It’s a shame that he’s become the face of Japan to many westerners. He’s not really Japanese. Did you know that he says he found his voice by writing the first pages of first novel in English – then translating them into Japanese? As he gets older, his readers get younger. He’s a commercial writer, a sell-out. Not real literature.”

I sighed quietly, but said nothing.

“I sound like I’m bitter, right? It’s just that I’ve tried all my life to create beautiful, Japanese prose. I remember when Haruki and I were dating we talked about books all the time, about beautiful books and beautiful prose. Now he churns out vague, stinking butter.”

“When’s the last time you met him in person?”

“A few years ago. I forgot exactly when. It was in a small town outside of Kyoto.”

I quickly shook my head. I wondered if I should bring up the story of my meeting with Murakami in a small town of outside of Kyoto, three years ago.

“Hmm.”

She looked suspicious. I knew it was risky, but there was one more vital question I had to ask.

“What did you talk about?”

“He told me he had just met with an American writer and was feeling inspired.”

“Inspired?”

She shook her head. “Yeah, but the conversation was boring, as usual, I don’t remember anything else. He talked a lot.”

Did Murakami meet her soon after our meeting? Maybe even the day after? Did he actually use my experience with him, then his experience with her, to write another boring book? Or was I making this all up in my head, and going crazy?

I really didn’t want to think that Murakami was writing book after book using experiences with women from his past and nobody-writers. But he told me, quite matter-of-factly, that having seven women from his past was plenty of enough material, and that he was satisfied simply living out his remaining years quietly, occasionally vising that little town. And he’d seemed to mean it. But maybe Haruki had a chronic psychological condition, one that reason alone couldn’t hold in check. And maybe his illness, and his dopamine, were urging him to just do it! And perhaps all that had brought him to contact old girlfriends and nobody-writers, a pernicious habit.

Maybe I’ll try it myself sometime. On sleepless nights, that random, fanciful thought sometimes comes to me. I’ll take a memory of a woman who I used to be with, focus on it like laser, contact a nobody-writer, then use a conversation about the process to pull dream-like, abstract literature out of me. What would that feel like? Could I also sell millions of books?

No. That’ll never happen. I’ve never been skillful at weaving vague, dream-like paragraphs that have no sense but exude a bizarre atmosphere that tickles the fancy of western, literary critics. And I don’t care about the women from my past. Even if I could do that, readers would think I was just copying Murakami, because he did it first.

Extreme love, extreme loneliness. The time-worn tropes. Even since I met Murakami, whenever I hear someone name-drop a classical composer who I’ve never heard of then spend ten minutes praising a symphony, I think of him. I picture the elderly, famous writer in that tiny, decrepit town, jumping out of the bushes, asking me “How is the thing?” And I think of the snacks – the kakipi and the dried squid – that I consumed as we drank beer together, propped up against the wall, while Haruki droned on and on.

I haven’t seen the beautiful, elderly travel-magazine editor since then, so I have no idea what fate befell her after that, or if she’s dead. I hope she never learned that Murakami uses their past experiences together for literature. She was blameless, after all. Nothing was her fault. I do feel bad for her, but I still can’t bring myself to tell her, if she’s still alive, about what Murakami is doing. Then again, she probably wouldn’t care, anyway, since she doesn’t read his boring books and calls them stinking butter.

Subscribe below