This story has been published in a book called Not Who I Pictured: Sixteen Photographs Sixteen Stories, which you can buy here for $9.99

Below is the first half of the story (2 minute read). If you’re still uncertain about buying the book, I’ve also posted two passages from other stories, below mine. I hope you enjoy them.

If you don’t have cash to spare, but still want to read my story to the end, contact me directly. I’ll send you the whole piece.

When Tino DeAngelis died, my grandmother called my mother and mentioned his death, and that there wasn’t a funeral or a wake for him. My grandmother was always private about her relationship with Tino. But my mother went to her house anyway after the phone call, without telling her she was coming. When my mother arrived, my grandmother cried, saying,

“You came.”

Tino was seventy one when he met my grandmother. He was renting her sister’s house. My grandfather died a few weeks after he moved in. Tino sent an extravagant bouquet of flowers to my grandfather’s wake. Then he began taking my grandmother out to dinner.

Tino and my grandmother kept seeing each other. She retired after working for forty years at a mental hospital. Tino liked to drive and took my grandmother on many trips. They took me on a trip to Canada when I was two years old. Tino must have been a wonderful person to spend time with for my grandmother who was, after all, a widow living in the town of Ovid, in upstate New York, where there was not a lot of adventure. Tino was full of adventure. He took my grandmother to Rome, Paris, Colorado, and bought her jewelry. They read books and planted flowers together.

My family doesn’t know the details of how their relationship began. But when my parents met Tino for the first time, he pulled them aside and said, “There are some things you should know about me…about my past.”

My earliest memories of Tino are seeing him with my grandmother on Christmas Eve, when my family would always go to my grandmother’s house. He was a short, stocky man with bulging eyes and a wide smile who was always shuffling around the kitchen. He would cook steak sandwiches, make my uncle champagne cocktails, shake my hand with a vice-like grip, and tell stories. He would call me a champion. He bought me my first racing bike with my named engraved on it, played handball with me when I was eight, and wrote me twenty five letters.

In one he wrote,

Dear Pal Jack,

God Bless You, young man. I hope this note finds you doing well in every way possible. Grandpa thinks of you every day and I just want you to know that I cannot wait until the day you reach the age where you have a driver’s license; I am going to get you a new Honda.

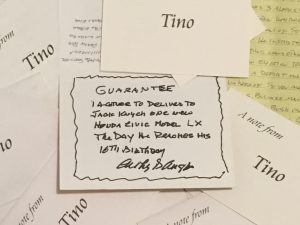

Despite writing in an informal contract: “Guarantee: I agree to deliver to Jack Knych one new Honda Civic model LX the day he reaches his 16thbirthday,” I never saw the car. But I loved Tino nonetheless, and I didn’t mind when he called himself Grandpa Tino. My family loved Tino as well.

But my grandmother’s relationship with Tino would be tested in 1992, when the F.B.I. invaded her home to arrest Tino for using $660,000 of forged letters from the Savings Bank of the Finger Lakes to purchase more than $1 million of pork from a Canadian firm. He would be convicted and sent to prison for the third time.

*

In 2010, a year after Tino’s death, I was in college pulling an all-nighter for my Financial Economics class. I was reading a book on the history of the stock market, when I came across a chapter on Tino. I almost fell out of my chair. I learned that he had almost caused the stock market to crash in 1963 by committing the most notorious white-collar crime in American history at the time, and that he had been a millionaire in the 1950s and 1960s. I remember thinking, “Was this really the same man who had been in love with my grandmother? Was this the same man who I had a picture of on my dorm room wall, posing ridiculously on an old-fashioned bicycle? And if so, who was he?”

The next day I called my father and had the truth of Tino’s crimes confirmed. When my father met Tino in 1985, he had been uncertain whether Tino was telling the truth concerning his criminal past, so my father went to the Bird Library at Syracuse University to check the newspaper archives to verify Tino’s story. Sure enough, Tino had been on the front of page of The New York Times for what called the “Salad Oil Swindle.” He had served seven years in federal prison for defrauding his clients for over $150 million (equivalent to $1.2 billion in 2018). For the next eight years I would intermittently research Tino’s life, to try and learn more about the man who tried to marry my grandmother.

*

Anthony “Tino” DeAngelis was born in 1915 in the Bronx, the oldest son of Italian immigrants. “Tino” translates to “endearing little fellow of the angels.” He grew up in poverty in a cold-water flat with four younger siblings. When interviewed by journalists later in life, Tino would reflect upon his childhood and say, ‘I wanted to do one thing in life – make a success. Even as a little kid, I partook very little of the gay life.”

Tino quit school at sixteen. Soon after, he borrowed $500 from his father, which he invested in a candy store. The candy store failed.

After the candy store went under, Tino would begin working as a helper at a meat market. One of the stories he would tell my family on Christmas Eve was about when he first saw a bicycle in a store. He told his mother,

“Let’s buy it,” and convinced the man behind the counter to give him the bike. “My father has a dependable job on the railroad,” he told the man. “We’ll pay through installments.” When Tino left the store with his mother and the bike, his mother said,

“Jesus Christ, Tino, your father is gonna kill me.” But Tino paid off the bike.

Within three years of working at the meat market, Tino had risen from helper to manager. By the age of twenty, he was managing two hundred employees.

When asked about being a manager at the age of twenty, Tino would reply, “There were always jealousies and stubbornness. But nothing deterred me. I’ve always had a brilliant and productive mind.”

*

Pragya Krishna wrote about her parents’ arranged marriage. Here’s an excerpt:

She [Pragya’s mother] had three older sisters, who’d all been married off, but she hadn’t really thought about the possibility that she was next.

When her brother’s wife saw she’d come home, she said, “Pinky,” (my mom’s nickname), “Take an hour to rest and then get dressed-up. There’s a boy coming to see you.”

“And I was so angry,” my mother recalls. “I said I don’t want to meet anyone. I had no decent clothes, I’d put on weight because I’d been binge-eating parathas because of the stress from studying. I was like, my hair’s like this, I don’t want to meet anyone.” But after her outburst, she calmed down as she always does, and obeyed, because that was what she did, especially if her parents had told her to do something. And these were her parents’ directions by proxy. “I said fine, and we started looking through my wardrobe. I found an old dhoti-type suit and I said, I’ll wear this.”

The boy arrived soon after and sat down in the living room. He had come with a friend. “I didn’t even know which one of them was the boy in question,” my mother says. She went into autopilot. Guests are supposed to be treated with courtesy, so she acted accordingly.

“Someone’s come to the house, I’m supposed to be an attentive hostess and be nice. ‘Please, have these rasgullas. I insist.’

“The young man in question, she says, had thought he didn’t want to marry a doctor. His friend, who is known to be tactless, said to her, “What if you were asked to forget you’re a doctor after marriage?”

She bristled.

The young man, however, intervened and said to his friend, “What kind of question is that? How would you feel if you were asked to forget you’re a scientist?”

“So then I thought, alright,” she says. “The guy has good sense.”

The rest of the conversation was just small talk, and when it was done my mom went back to her room and forgot about the whole thing. The young man came back later and picked up some pictures of her — a common practice during the arranged marriage process. “I didn’t know about it at the time,” my mother told me. “I was back to studying again. I paid no attention.”

But then, she says, “Exams were done, and my brother was like, okay, now you’re getting married.”

*

Chloe Picchio wrote about her grandfather, who grew up in a Pennsylvania mining town, became a soldier in hopes of experiencing adventure, then had his life shattered by the horrors of WWII:

Scranton, the county seat, soon became a symbol of the early 20th century’s hunger for wealth, like a character from the Great Gatsby who couldn’t spend their riches quickly enough. It was known as the “Electric City,” earning its nickname through the first-ever electric streetcars rolling down the avenues leading to an exotic menagerie of elephants and tigers at the local zoo. Five miles away, in Olyphant, those luxuries seemed like distant fantasies. Mining, even a generation removed from the underage breaker boys crushed to death under their coal carts, was dangerous and deadly. Anthracite mining required more blasting and deeper tunnels than those for bituminous coal, creating fragile coal seams where any small mistake became amplified with grave consequences. Explosions happened regularly, ignited by the little spark from a miner’s lamp or pipe. Hundreds of men died the year of my grandfather’s birth, their deaths by suffocation and gas explosion distilled into insurance company columns focusing on issues of liability and fault. This was all for $7.53 a day. The miners existed precariously at the bottom rung of the middle class, one workplace injury away from financial ruin. Still, it was enough to feed a family in the midst of the Depression, and the abundance of the coal fields was an exception in a country filled with homelessness and dust storms. Everyone in town worked in the mines whether they liked it or not. The earth underneath Olyphant’s main streets would occasionally buckle, the reverberations of a mining accident bubbling towards the surface, engulfing a home, a car, or a dream. My grandfather refused to be pulled underground with them. He wanted more…

…I always felt like my grandfather’s military service was an enigma. Throughout my childhood, it came in flashes, a brief viewing of his Purple Heart on Veteran’s Day or in the expensive patriotic floral arrangements my grandmother ordered without fail for his shelf in the mausoleum each Memorial Day. No one ever talked about what he actually saw because he rarely spoke about anything. Information dripped out like a leaky faucet, the discoveries infrequent but telling. Homemade jug wine prompted my great uncles to divulge that my grandfather had been in D-Day, painting a dramatic picture of how he stormed the beaches of Normandy, rivaling the opening sequence of Saving Private Ryan. That glory was tainted with awkwardness as they chuckled about how my grandfather had lied about his age, was caught, sent back to finish high school, and promptly returned to the army. Yet no one questioned his choice. Anyone who witnessed my grandfather’s decision is now either dead or ill. But in the end, it really doesn’t matter. What matters is what he saw and could never unsee….

*

To buy the book on Amazon, click here

More excerpts on the Medium Page

Listen to the Podcast

Subscribe below: