1 minute read. Exercise for my memoir writing class:

I’m sitting on a stone bench in the Staten Island Ferry Terminal next to a woman with purple hair. We’re both drinking beer and waiting for the boat.

“I’m serious, Sylvia, about working as soon as I arrive at my place,” I say. “You can stay over, but I’ll be writing.”

“Fine,” Sylvia says. “I won’t bother you.” Sylvia and I met through Tinder a week ago. She drove two hours from New Jersey to a bar near my apartment. After the bar, while walking back to my apartment, she confessed that she had been abused by her father, kicked out of her house, and was staying with friends. The next morning, while I was making breakfast, she also confessed that she desperately needed a job. An employee at my bar had recently quit and we needed a cashier for The Beer Corner, so I offered her the position. I knew this was dangerous and would likely crash and burn, but Sylvia was struggling.

“Why do you have to work tonight?” Sylvia asks me while on the boat.

“An editor is interested in one of my stories. I have until midnight to revise and submit again.”

“Oh…”

On the other side we walk a mile along the north shore. It’s a cold, clear night. Sylvia is skinny and doesn’t have a jacket, so I give her mine.

“Are you sure?” she asks.

“I don’t mind the cold.”

At my apartment I’m greeted by my bulldog, Hank. I pat him on the back, take off my dress clothes, and don my bathrobe. My studio is bare. There’s a bookshelf, a desk, a chair, a doggie bed, stacks of journals against the wall, and a mattress on the floor.

“Why doesn’t Hank say hello to me?” asks Sylvia.

“He doesn’t know you yet.” I sit at my desk.

“I didn’t notice these before,” Sylvia lies as she picks up one of my journals. “There must be over a hundred…” She begins to read.

“Don’t read those.”

“Why not?” She laughs. “You’re like a sixteen year-old girl.”

“I know.”

She walks over to the mattress. I don’t remember how much time passes at this point. It could have been five minutes or an hour. But while typing I hear,

“Jack?” I turn and see Sylvia sitting naked on the mattress. She has a strange smile and does an odd stretch. I feel the lust flame, but it fades. I realize that sex, like money, gains an exaggerated importance when you don’t have it. But when it’s there, and you’re not in love, it doesn’t mean much. I sigh and know this isn’t going to be good.

“Sylvia, I told you, I have to finish this.” Her eyes widen.

“Are you fucking serious?”

I should have shut up. Justification in these kinds of situations is futile. “I don’t want to work in restaurants for the rest of my life.”

“You gotta be fucking kidding me.” She starts jerkily putting her clothes back on. “I’m leaving.”

“Okay.”

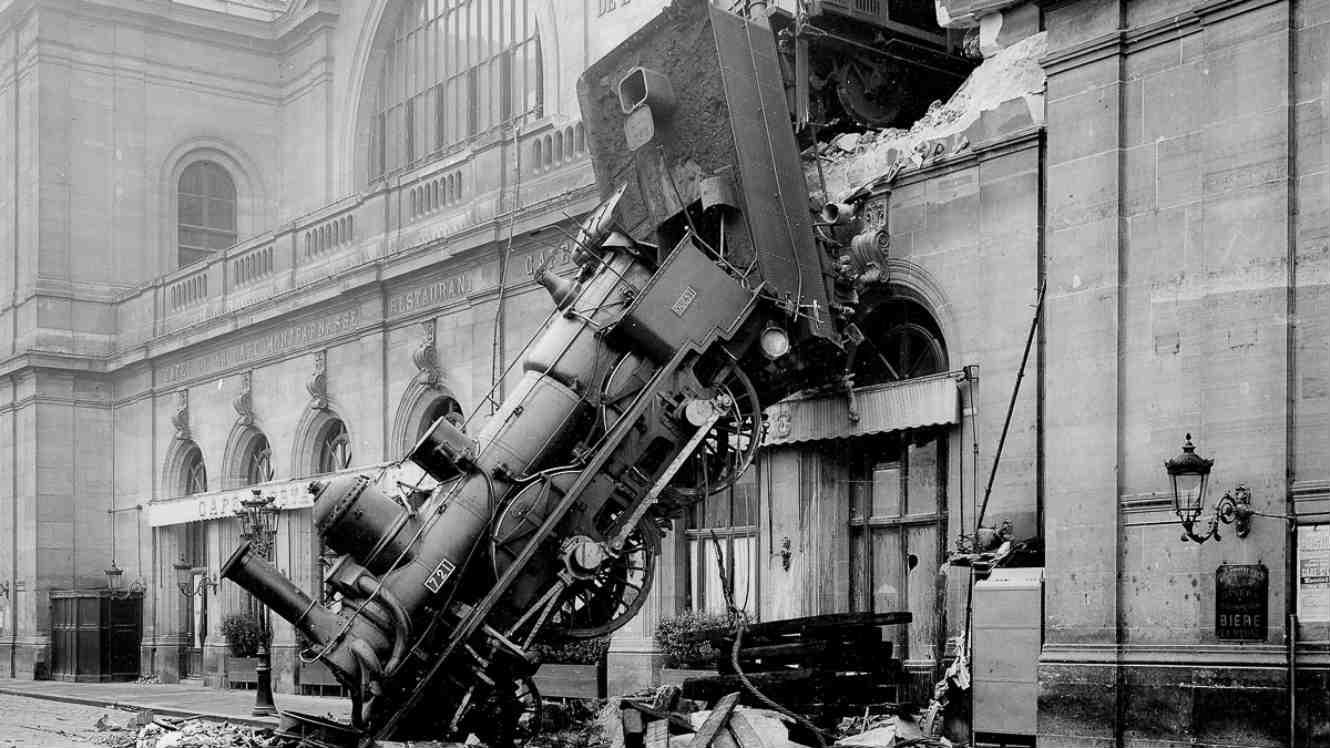

“You’re not even that good at fucking.” She stands up and pushes the bookshelf over. It hits the floor with a crash. Sylvia walks over and thrusts her middle finger in my face. For some reason I feel like I’m at a high school dance.

“Fuck you.” She kicks over a stack of journals, walks out, and slams the door. I sigh, walk over to the entrance, click the dead-bolt, and pick up the scattered books.

The next day the editor would reject the story. I would never hear from the woman with purple hair again.

Subscribe below: