(5 minute read)

(Thank you to Eric Berger and his book, Liftoff, my principle source for this essay)

In this year of our technological overlords, 2026, SpaceX as a company is going public. It is estimated to be worth $800 billion. The achievements of SpaceX have single-handedly brought down the cost of sending objects into orbit by a factor of five. Let’s look at how this all happened, through their initial failures and first success:

Once upon an imploding star, in May of 2002, Elon Musk founded SpaceX. Five months later, in October of 2002, Elon Musk received $175.8 million from selling PayPal. Now he had a significant chunk of Monopoly money to design and build rockets.

After a failed trip to Russia to buy missiles (ICBMs), in which the Russians laughed in his face, spit on his shoes, and tried to rip him off (they originally wanted to charge $8 million/missile, but during negotiations suddenly raised the price to $21 million/missile), Musk and SpaceX spent the next three years developing the Falcon 1 rocket. He hired the best engineers possible. A typical query by a propulsion chief, during an interview, was making sure the candidate knew how gas behaved in the intense environment of a rocket engine. The Merlin engine development occurred entirely in-house. SpaceX funded its own remote launch site at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshal Islands:

Failure 1: March 24th, 2006

Failure Time: ~33 seconds after takeoff

Cause: A small B-nut which had not been properly tightened on a kerosene fuel line. John Hollman (Launch operations) and Eddie Harris (structures engineer) had removed and reattached this B-nut to access an igniter valve that needed rewiring. This aluminum B-nut [cost: $5] on the fuel pump inlet pressure failed, not only due to improper tightening, but because of inter granular corrosion cracking; corrosion from sea salt spray on Omelet (the island) the night before. The B-nut ignited and triggered an engine fire. NBC News headline: SpaceX rocket failure traced to bad nut.

Back to the drawing board. One year passes…

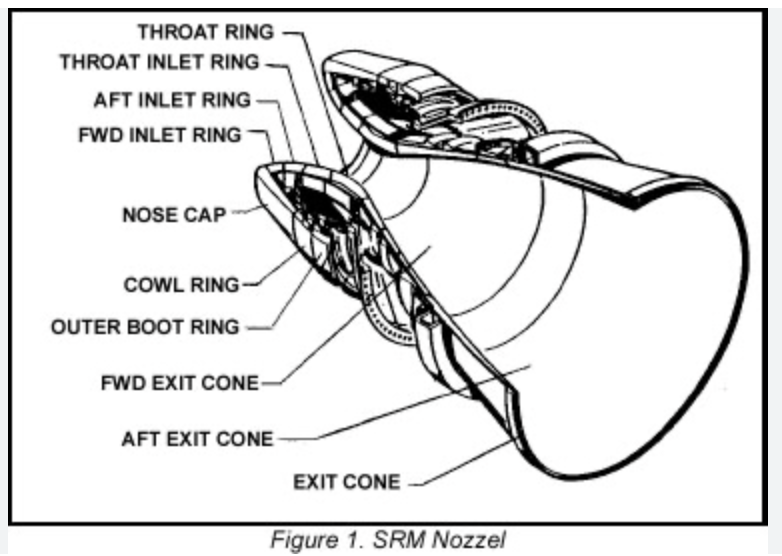

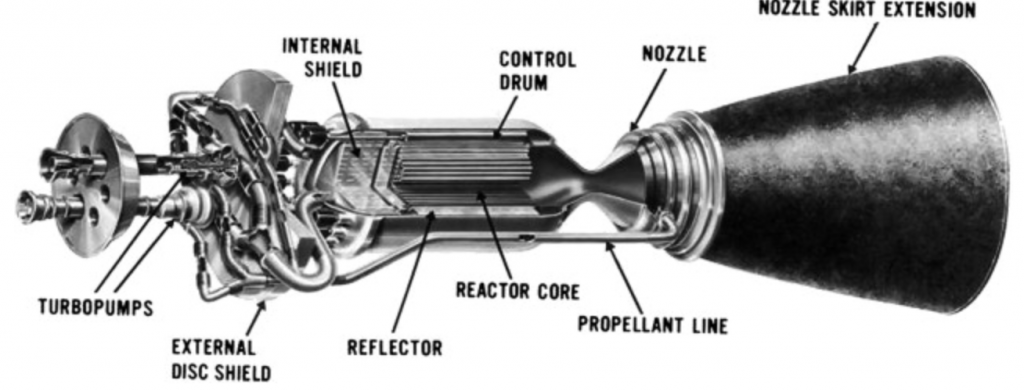

Intermission: The ablative nozzle caused SpaceX hell.

It is made of something akin to fiberglass, the ablative fabric is a resin mixed with silicon fibers. The fate of SpaceX was hanging on these [ablative] chambers. $30,000 a pop, manufactured by another company, prevents nozzle from melting from super hot flames. They had to do “basic pressure test” after “basic pressure test,” $30k after $30k. With chamber after chamber, the ablative coating would bubble, then crack. Musk had an idea: perhaps if they applied epoxy to the chambers, the sticky, glue-like material would seep into the cracks, then cure, solving the problem. Musk stayed up all night, missing an Xmass party and ruining a $2k pair shoes, with workers applying epoxy to the engine chamber. Didn’t work. The exhausted engineers and technicians working all night with Musk still admired his “willingness to jump into the fray, and get his hands dirty by their sides.”

Failure #2: March 21, 2007

Failure Time: ~5 minutes after liftoff

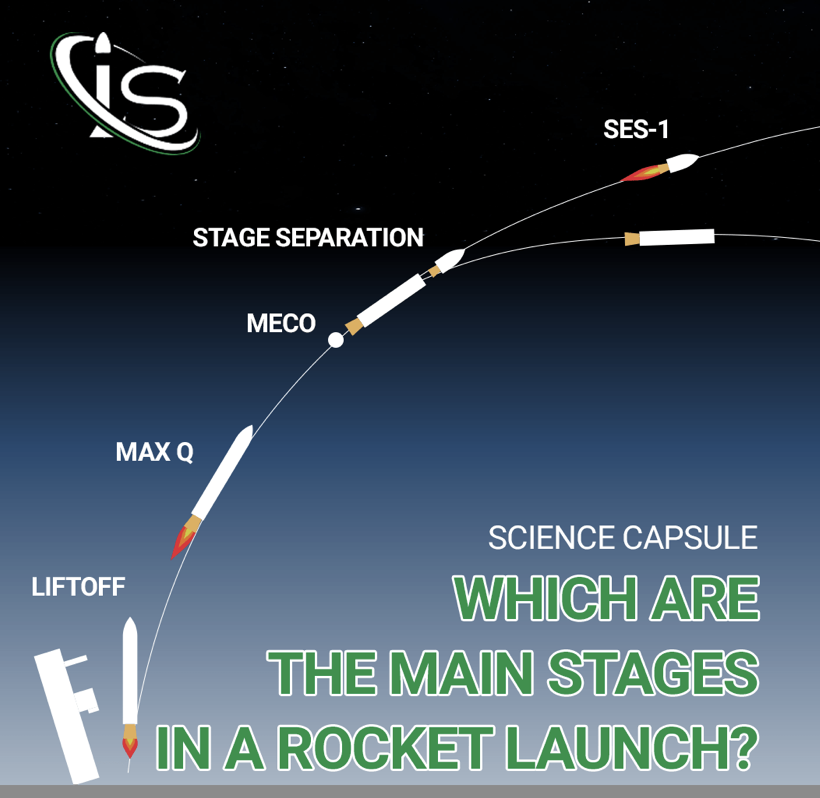

Cause: Residual Thrust after Engine shutdown, caused state separation failure

The main engine shut down normally, but there was remaining thrust that pushed the first stage into the second stage of the rocket. The stages collided instead of separating. The vehicle lost control and was destroyed. Hans Koenigsmann, Vice President of Flight Reliability for SpaceX, acknowledged that he and everyone else had missed the threat of residual thrust.

The shutdown dynamics weren’t fully modeled. Basically, when you test a rocket engine on the ground, the ambient air pressure is 15 psi, so if the rocket chamber has a pressure of 10 psi due to residual thrust, you just don’t see it in the data.

In the vacuum of space, however, with rocket hardware so close, even a minuscule thrust is enough to force a catastrophic collision between stages.

One year, five months pass…

*Flight 3 was delayed, however, because of a crack in the engine skirt due to courier driver hitting a pot hole when delivering it between airports.*

Failure #3: August 3, 2008

Cause: The first stage re-contacted the second stage, again caused by excessive residual thrust, but worsened by timing and “software control logic.” The engineers just couldn’t test the problem adequately on the ground.

The engine thrust tail-off lasted longer than expected. Separation occurred too early. The First stage clipped the Second stage. The Second stage spun uncontrollably.

A single line of code had derailed the rocket.

Since only a single line of code had caused the failure, Musk pushed for the next attempt A.S.A.P.. This was their last chance; they only had the hardware left for one more rocket and six weeks to launch it. For Flight Four, all SpaceX had to do was add four seconds to the time between main engine cutoff and stage separation. However, there was a chance that there would’t be a Flight Four. In addition to the time crunch, Musk’s money was running out. Tesla was on the brink of collapse amid a global financial crisis. I broke my ankle falling through the roof of a school. Musk’s marriage was falling apart. In September of 2008, after eight years of marriage, with 4-year-old twins and 2-year-old triplets, Musk filed for divorce. He was vomiting at night from the stress, as his entire fortune from PayPal had been invested in these two companies ($100 million into SpaceX, $75 million into Tesla), which both teetered on the edge of bankruptcy.

Normally, the parts of a Falcon 1 would be shipped from the U.S. to the Marshall Islands by sea, wrapped up like this:

But this sea transport took 2-3 weeks. SpaceX didn’t have that time. A rocket, their last chance, was flown from the U.S. to the island in an Air Force plane (C-17). But the manual provided to SpaceX, concerning how the plane operated, was outdated, and the descent and depressurization rates for C-17 on the charter flight were significantly more aggressive than the figures provided in the manual.

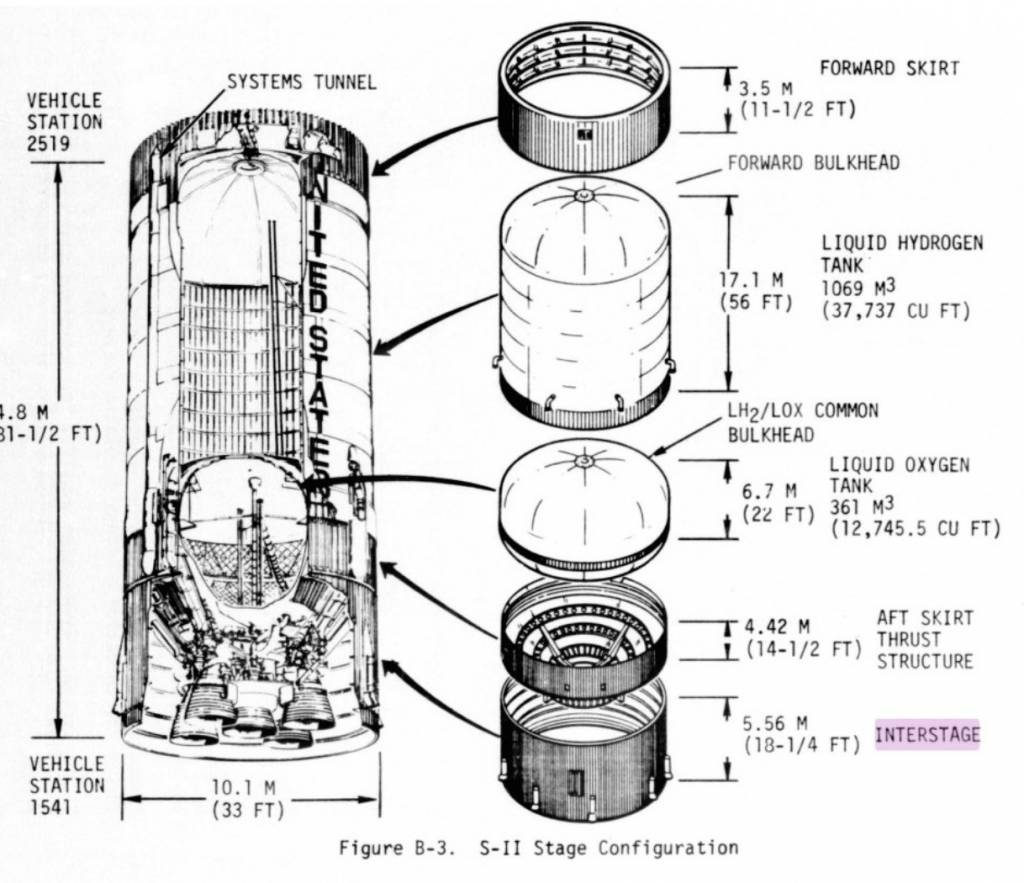

As the C-17 lost altitude to land, the LOX tank of the rocket (liquid oxygen fuel tank, which only had a small opening, a one-quarter inch fuel line that went though a desiccant so that no moisture got into the rocket) suffocated, and the rocket imploded. The crew heard “loud, terrible popping noises.”

The last rocket of SpaceX was crumpling. The SpaceX engineers’ faces went white as ghosts. One engineer started crying. The structure of the rocket “caved in, one loud ping after another, as if some giant were slowly squeezing a beer can.” They rushed to the front of the craft.

The pilots had a decision to make. They had a $200 million aircraft with two dozen lives and an imploding rocket aboard. They were thinking it would be safer to just open the plane’s large rear door and jettison the unstable rocket into the ocean below. (They would have done this if the SpaceX engineers weren’t there.) But the SpaceX team said, “Increase altitude, climb back up. We’ll fix this.”

“By the way,” the pilot said, “we only have thirty minutes of fuel.” The SpaceX team had ten minutes before the aircraft would restart its descent. They had to solve this problem or SpaceX as a company was toast.

The SpaceX team in the C-17 went back to the rocket and started pulling all manner of knives out of their pockets, then began cutting into the white shrink wrap over the rocket.

They needed more tools. The C-17 “loadmaster” gave them a tool chest: it contained a flathead screwdriver and a single crescent wrench. This, at least, allowed the technicians to open a couple of small lines. But to adequately equalize the pressure inside the rocket with that of the cargo bay, somebody needed to open a large pressurization line leading into the liquid oxygen tank. This could only be accessed by climbing into the rocket’s interstage.

The rocket continued to implode, thousands of feet above the ocean. All hell was breaking loose. Zach Dunn stepped forward.

“I’ll go in.” He turned to his friend, Mike Sheehan. “If the rocket starts to blow, pull me out.” He held a wrench and crawled into the interstage. Darkness surrounded him as he moved slowly, deeper in, along the wall. Sheehan’s hands held on to Dunn’s ankles. As Dunn moved, sharp components lining the exterior structure scraped his back, and the tank continued to pop and ping.

Dunn reached the pressurization line and managed to use the wrench to twist it open. To his relief, he heard air whooshing into the rocket.

“Take me out!” Sheehan yanked Dunn back across the tangle of pressurization lines and valves, which ripped into Dunn’s body.

The rocket hissed as it repressurized. Before the engineers’ eyes, the metal stage began popping back into its cylindrical form. Did this mean the rocket was a lost cause? The aluminum skin had never been intended to flex like this, as a rocket should never be exposed to higher external pressure.

“We all thought we were done,” Chinnery said. “The tank had imploded. We were devastated.”

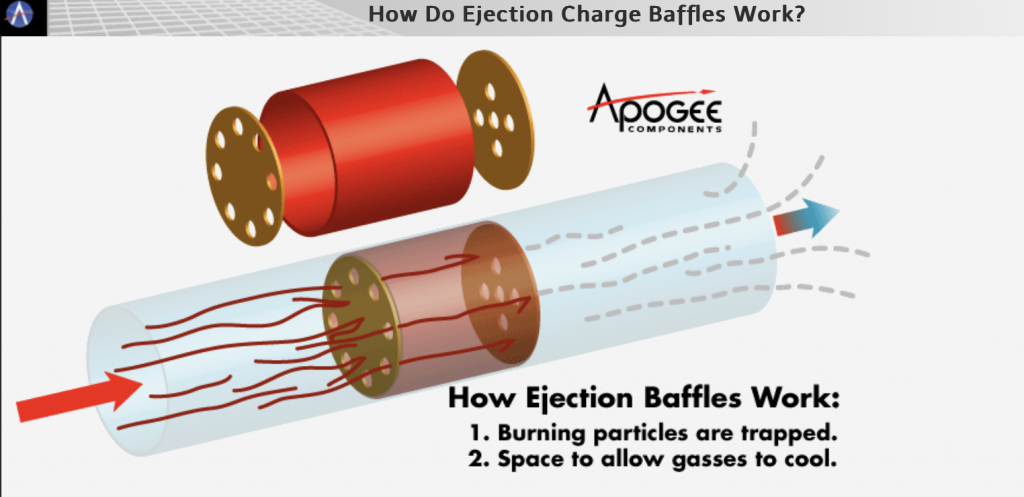

A few days later, a tiny camera attached to flexible tube, known as a borescope, was inserted through a sensor port into the first stage to assess the damage. About ten engineers crowded around a tiny screen as the probe snaked around inside the LOX tank. A baffle had been torn out of its bracket.

“That was the moment,” Dunn said, “when we knew for sure the rocket needed surgery and that we were screwed.”

Chinnery estimated it would take six weeks to take the first stage apart, inspect the damage, fix it, test it, and get back on track to launch. Chinnery presented the plan to Buzza. Buzza and Thompson shared it with Musk.

“Elon saw that and went off the frickin’ deep end,” Thompson said. Six weeks was too long. SpaceX didn’t have six weeks. Realistically, SpaceX did not even have a month before its funding ran out. Musk believed the rocket could be made functional.

There was no time for quality control or meticulous records. They did not have six weeks. They had one.

Back in Hawthorne, Texas, Thompson and Buzza grabbed all the hardware they might need (such as baffles, clips, and fasteners, and much more), then loaded Musk’s Dassault Falcon 900 jet down with supplies on Saturday. (Musk was busy at Tesla, sleeping on the factory floor, the Tesla Roadster production line was failing repeatedly, especially the transmission: he had pumped his last remaining $20 million liquid cash into the company, in order to pay suppliers for the next few weeks, but if Tesla didn’t receive $40 million from investors in October, the company would fail. If the Flight #4 didn’t work, confidence would fall, and investors were unlikely to give any more cash to Musk).

On Monday the Falcon 900 jet landed in Kwaj, but there was a skeleton airport crew that checked the flight in, and allowed Buzza and Thompson to check out, but told them that they couldn’t unload their plane until the next day. There was no time to wait. Buzza and Thompson drove down the road outside the airport, noticed an open gate near the jet, drove their truck through the gate and up to the plane, and unloaded the cargo themselves.

On the island there was a thrumming whirlwind of activity. An engineer’s emergency room flooded with structural-engineering patients with gunshot wounds. To support the one-thousand-pound engine, Ed Thomas had fashioned a makeshift platform from some wooden blocks. In the span of a single hour, they had stripped the rocket and put its engine on blocks.

Broken slosh baffles were replaced, welds inspected, lines straightened. Within less than a week, they buttoned the first stage back up.

“We knew full well that if anything failed, it was game over,” Thompson said. But in a week a small group of engineers and taken apart a rocket, then put it back together. That’s incredible and unprecedented. This process takes NASA months, without the pressure of a financial guillotine about to the chop off the head of the organization. Then again, this story reminds us: pressure in the brain, rather than a LOX tank, can be good.

After pressure tests, which went well, they bolted the second stage on to their first stage. Then the launch team rolled the entire rocket, the very last Falcon 1 hardware they had to use – out to the launchpad. By the last week of the month, they were as ready as they were ever going to be. It was all or nothing.

Flight #4: September 28th, 2008:

Success. Falcon 1 became the first privately developed liquid fuel rocket to reach Earth orbit. SpaceX was awarded a $1.6 billion Commercial Resupply Services contract with NASA. Thanks to…

(Delayed stage separation)

(Added settling thrusters)

(Improved shutdown modeling)

(Update flight software logic; i.e. they fixed that single line of code)